Search

Search our 7.980 News Items

CATEGORIES

We found 4 books in our category 'CLIMATE'

We found 6 news items

We found 4 books

KwaZulu-Natal

Savusa

2009

INT

condition: Very good, très bel état

book number: 202303011732

Climate change, carbon trading and civil society

Paperback, in-8, 231 pp., bibliographical notes, bibliography, index.

BOND Patrick (red.)@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

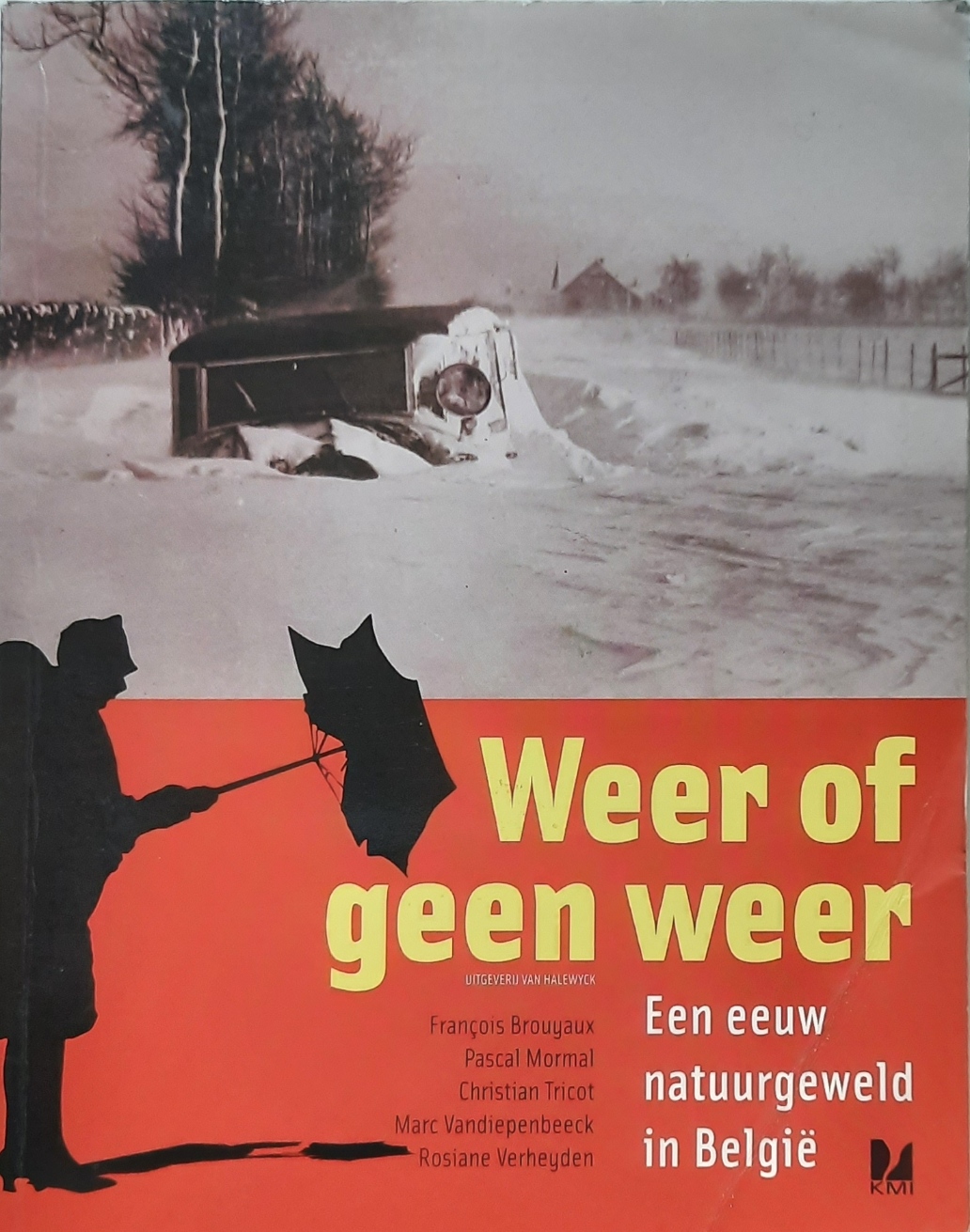

Leuven

Van Halewyck

2004

BEL

condition: Kreuk in de cover. Verder goede staat.

book number: 202107020145

Weer of geen weer. Een eeuw natuurgeweld in België (1901-2004).

Paperback, in-8, pp., illustraties, tabellen, bibliografie, lexikon.

Een echt kalendarium van zware onweders, zeer koude winters en verzengende zomers, overstromingen, hevige stormen en lange perioden van droogte.

Beslist geen vrijblijvend boek in een tijd van klimaatwijziging.

Het KMI te Ukkel bestaat sinds 1833.

Een echt kalendarium van zware onweders, zeer koude winters en verzengende zomers, overstromingen, hevige stormen en lange perioden van droogte.

Beslist geen vrijblijvend boek in een tijd van klimaatwijziging.

Het KMI te Ukkel bestaat sinds 1833.

BROUYAUX François, MORMAL Pascal, TRICOT Christian, VANDIEPENBEECK Marc, VERHEYDEN Rosiane@ wikipedia

€ 12.5

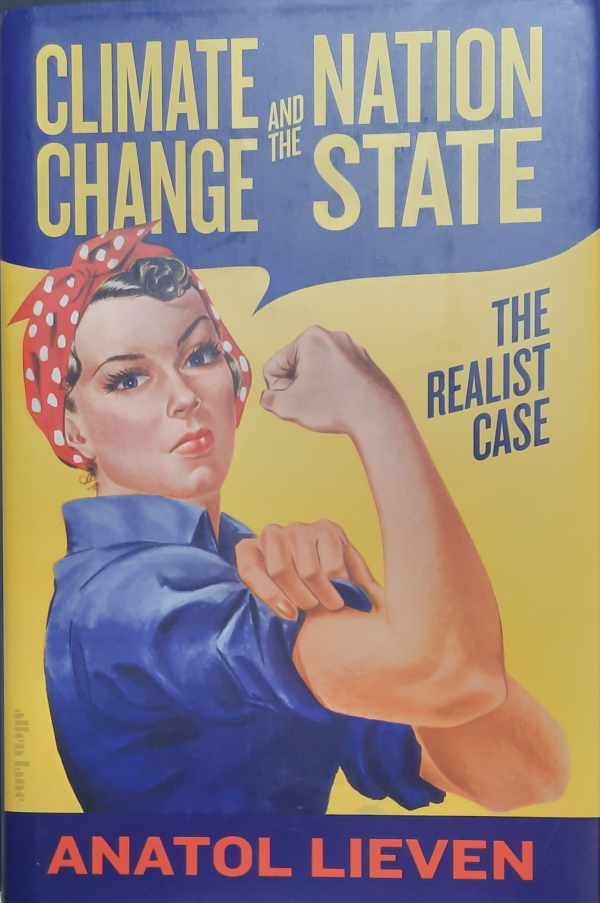

London

Allen Lane

2020

INT

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202212230108

Climate Change and the Nation State - The Realist Case

Hardcover, dj, in-8, 202 pp., no illustrations, bibliographical notes, bibliography, index.

In the past two centuries we have experienced wave after wave of overwhelming change. Entire continents have been resettled; there are billions more of us; the jobs done by countless people would be unrecognisable to their predecessors; scientific change has transformed us all in confusing, terrible and miraculous ways. Anatol Lieven's major new book provides the frame that has long been needed to understand how we should react to climate change. This is a vast challenge, but we have often in the past had to deal with such challenges- the industrial revolution, major wars and mass migration have seen mobilizations of human energy on the greatest scale. Just as previous generations had to face the unwanted and unpalatable, so do we. In a series of incisive, compelling interventions, Lieven shows how in this emergency our crucial building block is the nation state. The drastic action required both to change our habits and protect ourselves can be carried out not through some vague globalism but through maintaining social cohesion and through our current governmental, fiscal and military structures. This is a book which will provoke innumerable discussions.

In the past two centuries we have experienced wave after wave of overwhelming change. Entire continents have been resettled; there are billions more of us; the jobs done by countless people would be unrecognisable to their predecessors; scientific change has transformed us all in confusing, terrible and miraculous ways. Anatol Lieven's major new book provides the frame that has long been needed to understand how we should react to climate change. This is a vast challenge, but we have often in the past had to deal with such challenges- the industrial revolution, major wars and mass migration have seen mobilizations of human energy on the greatest scale. Just as previous generations had to face the unwanted and unpalatable, so do we. In a series of incisive, compelling interventions, Lieven shows how in this emergency our crucial building block is the nation state. The drastic action required both to change our habits and protect ourselves can be carried out not through some vague globalism but through maintaining social cohesion and through our current governmental, fiscal and military structures. This is a book which will provoke innumerable discussions.

LIEVEN Anatol@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Brugge

Marc Van de Wiele

1997

BEL

condition: Very fine

book number: 202105071001

De ogen van de panda. Een milieufilosofisch essay

9de druk. Pb met flappen, 72 pp., bibliografische noten.

Vermeersch durft te zeggen waar het op staat: een hoofdreden van de vervuiling van onze planeet is de OVERBEVOLKING, we zijn met teveel.

Het is een argument dat ondergesneeuwd is geraakt in de huidige (2021) discussies.

Het zogenaamde WTK-bestel (wetenschappelijk, technologisch, kapitalistisch) - tot stand gekomen in de 19de eeuw - heeft een dynamiek op gang gebracht die blijkbaar niet te stuiten valt. De componenten versterken elkaar. (28)

Het middel is doel geworden, het doel middel. M.a.w. de mens is niet meer het doel van de productie. "De doelloosheid, de irrationaliteit van het totaalsysteem wordt versluierd door de uiterste rationaliteit van de deelsystemen." (29)

Vermeersch durft te zeggen waar het op staat: een hoofdreden van de vervuiling van onze planeet is de OVERBEVOLKING, we zijn met teveel.

Het is een argument dat ondergesneeuwd is geraakt in de huidige (2021) discussies.

Het zogenaamde WTK-bestel (wetenschappelijk, technologisch, kapitalistisch) - tot stand gekomen in de 19de eeuw - heeft een dynamiek op gang gebracht die blijkbaar niet te stuiten valt. De componenten versterken elkaar. (28)

Het middel is doel geworden, het doel middel. M.a.w. de mens is niet meer het doel van de productie. "De doelloosheid, de irrationaliteit van het totaalsysteem wordt versluierd door de uiterste rationaliteit van de deelsystemen." (29)

VERMEERSCH Etienne@ wikipedia

€ 25.0

We found 6 news items

nations must cooperate or face collective suicide in the fight against climate change

ID: 202211081942

Humanity has a choice: cooperate or perish, Guterres told the UN COP27 summit.

It is either a Climate Solidarity Pact or a Collective Suicide Pact, he added.

It is either a Climate Solidarity Pact or a Collective Suicide Pact, he added.

ORG Explains 12: The UK’s Pivot to the Sahel

ID: 202001278833

27 January 2020

As the UK moves resources and personnel to the Africa’s Sahel region, we examine what the “pivot to the Sahel” is, why it is happening and what it will look like.

Author's note: Thanks to Zoe Gorman and Delina Goxho for their help with the piece (all the mistakes are the author’s own)

What?

During a speech in Cape Town, South Africa in September 2018, then-Prime Minister Theresa May laid out the UK’s new “Africa Strategy”, promising “a new partnership between the UK and our friends in Africa…built around our shared prosperity and shared security.” This new strategy was further fleshed out both by the former Minister for Africa, Harriett Baldwin, during an evidence session with the Foreign Affairs Committee (FAC) in March 2019 as well as in written evidence from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to the same committee’s inquiry into the UK’s Africa strategy.

All three have said that the strategy is made up of five key “shifts” or areas:

The first of these has been referred to as the UK’s “pivot to the Sahel” and – while this is just one aspect of the UK’s Africa Strategy – it has been an important change. The FCO’s written evidence to the FAC stated: “We will pivot UK resources towards Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania, which are areas of long-term instability and extreme poverty.” This has instigated a large uplift in staff (working both in Whitehall and in the region) and resources (including additional aid, military support and embassies) aimed at this region of the continent, including 250 soldiers to be deployed to Mali and new embassies opening in the region.

Where?

Definitions of the exact boundaries of the Sahel vary; however, according to Britannica, the Sahel is a “region of western and north-central Africa extending from Senegal eastward to Sudan. It forms a transitional zone between the arid Sahara (desert) to the north and the belt of humid savannas to the south. The Sahel stretches from the Atlantic Ocean eastward through northern Senegal, southern Mauritania, the great bend of the Niger River in Mali, Burkina Faso…, southern Niger, northeastern Nigeria, south-central Chad, and into Sudan.”

Figure 1 International engagement in the Sahel region (Image data source: Africa Centre Strategic Studies)

Why?

As the FCO recently noted, this is an area “where [the UK has] traditionally had little representation”. Mali, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mauritania were French colonies that gained independence in 1960. Even after this, France has maintained significant economic and political ties to the region. As such, the UK has previously conceived of this region as France’s domain. The recent “pivot to the Sahel” begs the question: why has the UK started working in this region?

1. Instability and threats to the UK

One reason for the UK’s pivot is to help address the instability that has engulfed the region in the last few years. In her Cape Town speech, Theresa May said the UK will be “supporting countries and societies on the front line of instability in all of its forms. So, we will invest more in countries like Mali, Chad and Niger that are waging a battle against terrorism in the Sahel.”

The Sahel is a region that has historically been troubled by weak governance, high levels of youth unemployment, porous borders, frequent drought, high levels of food insecurity and paltry development progress. Since the 2012 crisis in Mali, the region has also witnessed an escalation in jihadist activity and a burgeoning of illicit migratory networks and trafficking. The area is therefore the subject of increasing international concern, as ungoverned spaces could provide ‘safe havens’ for terrorist activity.

Seven years ago, in March 2012, Islamist groups gained control over the northern part of Mali. They had benefited from the instability (and the spread of weapons) following the Libyan civil war. Returning fighters after the fall of Muammar al-Gadhafi’s regime in Libya brought weapons and sparked a new rebellion under the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), some of these were tied to jihadist groups but others were not. Meanwhile, a political coup in Mali ousted President Amadou Toumani Touré, creating a momentary power vacuum. Northern Islamist groups Ansar Dine, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) also took up arms, driving the MNLA from strategic cities in Timbuktu and Gao regions. The absence or inability of the state to respond to growing insecurity has contributed to a proliferation of self-defence militias which may be party to one community or ethnic group, lack legitimacy and contribute to cycles of violence.

In January 2013 French forces intervened at the request of the Malian government to stop the groups advancing on Bamako (the capital of Mali) through a military operation called Opération Serval.

The same year, David Cameron, British Prime Minister at the time, said the French action in Mali was "in our interests" and the UK “should support the action that the French have taken." He promised that the UK would be "first out of the blocks, as it were, to say to the French 'we'll help you, we'll work with you and we'll share what intelligence we have with you and try to help you with what you are doing'."

The UK sent the following support to the French operation:

330 military personnel were deployed – including 200 soldiers going to West African nations and 40 military advisers to Mali

Two cargo planes (used to ship French military equipment to Mali) and a surveillance plane, supported by 90 support crew

None of these soldiers were deployed in combat roles; instead they focused on non-kinetic activity such as logistical support and training.

Opération Serval proved militarily successful in pushing jihadist groups back and stopping them from overtaking key airports. In 2014, the military campaign moved to a different stage with Operation Serval becoming Opération Barkhane. Broader in its purpose than Serval, Opération Barkhane was launched to provide long-term support to the wider region, in order to prevent ‘jihadist groups’ from regaining control. Opération Barkhane is a longer-term military intervention that operates not within a country, but over the countries of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger.

In the same year, Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz galvanised the creation of the G5 Sahel while president of the African Union. Bringing together Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger, the G5 Sahel joint force (FC-G5S) gained support from the African Union and United Nations, although the US has repeatedly blocked Security Council Chapter VII funding of the force. An agglomeration of 5000 military personnel, police officers, gendarmerie and border patrol officers from the five states, the FC-G5S undertakes operations in conflict hotspots in border regions between the countries to curtail terrorism, illicit trafficking and illegal migration. According to General Lecointre, the Chief of Staff of the French Armed Forces, France hopes that the FC-G5S will take over some of the responsibilities of Opération Barkhane – but the FC-G5S has been slow to operationalise.

The following year, in March 2015, the Malian government and coalitions of armed groups in the North agreed on a peace accord in Algiers following months of negotiations. Unfortunately, this agreement does not include jihadist groups or the multitude of armed groups flourishing in the centre, and its provisions have gone largely unimplemented.

The French government has also continued calls for help from regional and international actors. The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was established in 2013 to support political processes in the country and carry out a number of security-related tasks. It currently has 14 874 staff from nearly 60 countries. The European Union Training Mission in Mali (EUTM-Mali) also started in the same year, to strengthen the capabilities of the Malian Armed Forces. It is now made up of 600 soldiers from 25 European countries. More generally, the EU and its member states are projected to spend €8 billion on development assistance in the Sahel.

France, Germany, the EU, the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the United Nations Development Programme also launched the Alliance for the Sahel in July 2017 to coordinate donor activity. The UK – along with Italy, Spain and most recently, Saudi Arabia – have now joined the Alliance. In July 2018, the UK also announced its support to Opération Barkhane, sending three Royal Air Force Chinook helicopters (supported by almost 100 personnel.

In August 2019, France and Germany announced the “Partnership for Stability and Security in the Sahel” to bring together countries in the region and international partners to identify gaps in the counter-terrorism response. Operation Tacouba, a planned operation to reinforce Malian forces with European special forces, will also seek to support regional forces in their fight against jihadist groups.

Despite this, violence has continued, the northern region of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, have been suffering some of the deadliest attacks to date, with the area ravaged by inter-community conflict and attacks on military, peacekeepers and civilians. The number of reported violent events linked to militant Islamic group activity in the Sahel has been doubling every year since 2016 (from 90 in 2016 to 194 in 2017 to 465 in 2018). Added to this, there have abuses against civilians by state forces, for instance the Malian armed forces have been accused of shooting civilian market-goers and burning members of a pro-government self-defence militia. This has worsened the humanitarian situation. For instance, since January 2018, more than one million people have been internally displaced across the Sahel region.

In light of this continued instability, the UK is reassessing its engagement to help stem the violence. The FCO has suggested that: “Our efforts in the Sahel seek to contain threats to regional security and wider UK interests, and make migration safer while providing critical humanitarian support to those who need it.” Similarly, when announcing the UK’s most recent contribution to the UN mission then-UK Defence Secretary, Penny Mordaunt, said “[t]he UK is committed to supporting the international community in combating instability in Mali, as well as strengthening our wider military engagement across the Sahel region.”

2. Global Britain

The UK’s pivot to the Sahel is also part of the UK’s Global Britain strategy. This strategy is “about reinvesting in our relationships, championing the rules-based international order and demonstrating that the UK is open, outward-looking and confident on the world stage.” The Global Britain strategy is referenced throughout UK policy documents and public statements and is often seen as an attempt to demonstrate the UK’s global focus – especially in light of the UK’s imminent withdrawal from the EU. The pivot to the Sahel helps this strategy in two ways: it maintains international relationships (especially with European allies) and it coincides with the UK’s renewed commitment to the UN.

To the first of these, the focus on the Sahel is an important way of maintaining alliances with the UK’s (especially European) allies. For instance, the FCO has said the pivot to the Sahel will “support our alliances with international partners such as France, Germany and the [African Union] as we exit the European Union.” A number of officials we spoke to also argued that maintaining relations with France was a key driver for the UK’s renewed focus in the region; for example, one soldier in Kenya said of the pivot to the Sahel, “post-Brexit we need trade deals with France.”

Another aspect of this is supporting the UN. In September 2019, ahead of his trip to the UN General Assembly in New York, Foreign Secretary, Dominic Raab said: “As we make progress in our Brexit negotiations, we are also taking our vision of a truly Global Britain to the UN – leading by example as a force for good in the world.” The UK has exceeded its commitment to double its 2015 contribution of personnel to UN Peacekeeping operations, increasing their number from 291 to 740 by May 2018, and is now globally the sixth largest contributor financially.

There is already evidence of the UK’s commitment to the UN impacting the UK’s approach to the Sahel. For example, the UK has pledged £49.5 million to the UN mission in Mali as part of the UK’s regular contributions to UN peacekeeping missions. It is clear then that there will be a number of big changes in how the UK engages in this region of Africa. Below we set out some concrete changes that we might expect to see in the year ahead.

How?

It still remains unclear exactly what this pivot to the Sahel will look like, but it is likely to see a shift of British people and resources to the region. In the FCO’s own description of this shift, it listed a number of new funding streams, including:

£2.3 million of humanitarian aid across the region between 2015-19 (making it “the third largest humanitarian donor to the Sahel”)

£50 million to support climate change resilience

£30 million “to support education in the Sahel and neighbouring countries.”

To support these commitments, more UK personnel will be working (in the region and in Whitehall) on the Sahel. Harriet Matthews, Director for Africa at the FCO, noted that the UK Government has “expanded a joint unit on the Sahel” (a unit made up of people from different UK departments, such as the FCO, the Ministry of Defence and the Department for International Development) to oversee activity in the region.

The UK has also promised “an increased UK presence” in the Sahel. It has said that it will increase the size of UK embassies in Mali and Mauritania, open “a regional hub” in Dakar, Senegal, and establish new embassies in Niger and Chad. The FCO does not provide a specific timeline for these changes.

In one of her last acts as British Defence Secretary, in July 2019, Penny Mordaunt also announced that a long-range reconnaissance task group of 250 personnel will be deployed to Mali in 2020. These UK soldiers will be “asked to reach parts of Mali that most militaries cannot, to feed on-the-ground intelligence back to the [UN] mission headquarters.” This represents one of the biggest British peacekeeping deployments since Bosnia and it will be the most dangerous mission for British forces since Afghanistan. MINUSMA is the UN peacekeeping mission with the highest casualty rate in the world and, since its inception, 206 UN peacekeepers have been killed as part of it.

Internationally, the UK is also likely to play a greater role in conversations about the region. For instance, it is a member of the Sahel Alliance, which was set up by France, Germany and the EU to focus on increasing coordination between partners working in the region. The UK also aims to place “extra staff in Paris to work alongside the French government on the Sahel.” The UK has said that it hopes that engaging with other international partners more effectively will allow it to “drive forward progress on long-term solutions to the drivers of conflict, poverty, and instability.”

Want to know more?

This has been a brief overview of the key issues and considerations of the UK’s recent “pivot to the Sahel”, something which our team look at for its own work. You can read some more in depth pieces we have written on the pivot and what it means for UK foreign policy here:

Improving the UK offer in Africa: Lessons from military partnerships on the continent by Abigail Watson and Emily Knowles

Fusion Doctrine in Five Steps: Lessons Learned from Remote Warfare in Africa by Abigail Watson and Megan Karlshoej-Pedersen

Mali: Consequences of a War by Paul Rogers

Devils in the Detail: Implementing Mali's New Peace Accord by Richard Reeve

Security in the Sahel: Two-Part Briefing by Richard Reeve

The Military Intervention in Mali and Beyond: An Interview with Bruno Charbonneau

Libya: Between the Sahel-Sahara and the Islamic State Crises by Richard Reeve

From New Frontier to New Normal: Counter-terrorism Operations in the Sahel-Sahara by Richard Reeve and Zoë Pelter

Too Quiet on the Western Front? Counter-terrorism Build-up in the Sahel-Sahara by Richard Reeve

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

About the author

Abigail Watson is the Research Manager at ORG's Remote Warfare Programme.

As the UK moves resources and personnel to the Africa’s Sahel region, we examine what the “pivot to the Sahel” is, why it is happening and what it will look like.

Author's note: Thanks to Zoe Gorman and Delina Goxho for their help with the piece (all the mistakes are the author’s own)

What?

During a speech in Cape Town, South Africa in September 2018, then-Prime Minister Theresa May laid out the UK’s new “Africa Strategy”, promising “a new partnership between the UK and our friends in Africa…built around our shared prosperity and shared security.” This new strategy was further fleshed out both by the former Minister for Africa, Harriett Baldwin, during an evidence session with the Foreign Affairs Committee (FAC) in March 2019 as well as in written evidence from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to the same committee’s inquiry into the UK’s Africa strategy.

All three have said that the strategy is made up of five key “shifts” or areas:

The first of these has been referred to as the UK’s “pivot to the Sahel” and – while this is just one aspect of the UK’s Africa Strategy – it has been an important change. The FCO’s written evidence to the FAC stated: “We will pivot UK resources towards Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania, which are areas of long-term instability and extreme poverty.” This has instigated a large uplift in staff (working both in Whitehall and in the region) and resources (including additional aid, military support and embassies) aimed at this region of the continent, including 250 soldiers to be deployed to Mali and new embassies opening in the region.

Where?

Definitions of the exact boundaries of the Sahel vary; however, according to Britannica, the Sahel is a “region of western and north-central Africa extending from Senegal eastward to Sudan. It forms a transitional zone between the arid Sahara (desert) to the north and the belt of humid savannas to the south. The Sahel stretches from the Atlantic Ocean eastward through northern Senegal, southern Mauritania, the great bend of the Niger River in Mali, Burkina Faso…, southern Niger, northeastern Nigeria, south-central Chad, and into Sudan.”

Figure 1 International engagement in the Sahel region (Image data source: Africa Centre Strategic Studies)

Why?

As the FCO recently noted, this is an area “where [the UK has] traditionally had little representation”. Mali, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mauritania were French colonies that gained independence in 1960. Even after this, France has maintained significant economic and political ties to the region. As such, the UK has previously conceived of this region as France’s domain. The recent “pivot to the Sahel” begs the question: why has the UK started working in this region?

1. Instability and threats to the UK

One reason for the UK’s pivot is to help address the instability that has engulfed the region in the last few years. In her Cape Town speech, Theresa May said the UK will be “supporting countries and societies on the front line of instability in all of its forms. So, we will invest more in countries like Mali, Chad and Niger that are waging a battle against terrorism in the Sahel.”

The Sahel is a region that has historically been troubled by weak governance, high levels of youth unemployment, porous borders, frequent drought, high levels of food insecurity and paltry development progress. Since the 2012 crisis in Mali, the region has also witnessed an escalation in jihadist activity and a burgeoning of illicit migratory networks and trafficking. The area is therefore the subject of increasing international concern, as ungoverned spaces could provide ‘safe havens’ for terrorist activity.

Seven years ago, in March 2012, Islamist groups gained control over the northern part of Mali. They had benefited from the instability (and the spread of weapons) following the Libyan civil war. Returning fighters after the fall of Muammar al-Gadhafi’s regime in Libya brought weapons and sparked a new rebellion under the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), some of these were tied to jihadist groups but others were not. Meanwhile, a political coup in Mali ousted President Amadou Toumani Touré, creating a momentary power vacuum. Northern Islamist groups Ansar Dine, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) also took up arms, driving the MNLA from strategic cities in Timbuktu and Gao regions. The absence or inability of the state to respond to growing insecurity has contributed to a proliferation of self-defence militias which may be party to one community or ethnic group, lack legitimacy and contribute to cycles of violence.

In January 2013 French forces intervened at the request of the Malian government to stop the groups advancing on Bamako (the capital of Mali) through a military operation called Opération Serval.

The same year, David Cameron, British Prime Minister at the time, said the French action in Mali was "in our interests" and the UK “should support the action that the French have taken." He promised that the UK would be "first out of the blocks, as it were, to say to the French 'we'll help you, we'll work with you and we'll share what intelligence we have with you and try to help you with what you are doing'."

The UK sent the following support to the French operation:

330 military personnel were deployed – including 200 soldiers going to West African nations and 40 military advisers to Mali

Two cargo planes (used to ship French military equipment to Mali) and a surveillance plane, supported by 90 support crew

None of these soldiers were deployed in combat roles; instead they focused on non-kinetic activity such as logistical support and training.

Opération Serval proved militarily successful in pushing jihadist groups back and stopping them from overtaking key airports. In 2014, the military campaign moved to a different stage with Operation Serval becoming Opération Barkhane. Broader in its purpose than Serval, Opération Barkhane was launched to provide long-term support to the wider region, in order to prevent ‘jihadist groups’ from regaining control. Opération Barkhane is a longer-term military intervention that operates not within a country, but over the countries of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger.

In the same year, Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz galvanised the creation of the G5 Sahel while president of the African Union. Bringing together Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger, the G5 Sahel joint force (FC-G5S) gained support from the African Union and United Nations, although the US has repeatedly blocked Security Council Chapter VII funding of the force. An agglomeration of 5000 military personnel, police officers, gendarmerie and border patrol officers from the five states, the FC-G5S undertakes operations in conflict hotspots in border regions between the countries to curtail terrorism, illicit trafficking and illegal migration. According to General Lecointre, the Chief of Staff of the French Armed Forces, France hopes that the FC-G5S will take over some of the responsibilities of Opération Barkhane – but the FC-G5S has been slow to operationalise.

The following year, in March 2015, the Malian government and coalitions of armed groups in the North agreed on a peace accord in Algiers following months of negotiations. Unfortunately, this agreement does not include jihadist groups or the multitude of armed groups flourishing in the centre, and its provisions have gone largely unimplemented.

The French government has also continued calls for help from regional and international actors. The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was established in 2013 to support political processes in the country and carry out a number of security-related tasks. It currently has 14 874 staff from nearly 60 countries. The European Union Training Mission in Mali (EUTM-Mali) also started in the same year, to strengthen the capabilities of the Malian Armed Forces. It is now made up of 600 soldiers from 25 European countries. More generally, the EU and its member states are projected to spend €8 billion on development assistance in the Sahel.

France, Germany, the EU, the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the United Nations Development Programme also launched the Alliance for the Sahel in July 2017 to coordinate donor activity. The UK – along with Italy, Spain and most recently, Saudi Arabia – have now joined the Alliance. In July 2018, the UK also announced its support to Opération Barkhane, sending three Royal Air Force Chinook helicopters (supported by almost 100 personnel.

In August 2019, France and Germany announced the “Partnership for Stability and Security in the Sahel” to bring together countries in the region and international partners to identify gaps in the counter-terrorism response. Operation Tacouba, a planned operation to reinforce Malian forces with European special forces, will also seek to support regional forces in their fight against jihadist groups.

Despite this, violence has continued, the northern region of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, have been suffering some of the deadliest attacks to date, with the area ravaged by inter-community conflict and attacks on military, peacekeepers and civilians. The number of reported violent events linked to militant Islamic group activity in the Sahel has been doubling every year since 2016 (from 90 in 2016 to 194 in 2017 to 465 in 2018). Added to this, there have abuses against civilians by state forces, for instance the Malian armed forces have been accused of shooting civilian market-goers and burning members of a pro-government self-defence militia. This has worsened the humanitarian situation. For instance, since January 2018, more than one million people have been internally displaced across the Sahel region.

In light of this continued instability, the UK is reassessing its engagement to help stem the violence. The FCO has suggested that: “Our efforts in the Sahel seek to contain threats to regional security and wider UK interests, and make migration safer while providing critical humanitarian support to those who need it.” Similarly, when announcing the UK’s most recent contribution to the UN mission then-UK Defence Secretary, Penny Mordaunt, said “[t]he UK is committed to supporting the international community in combating instability in Mali, as well as strengthening our wider military engagement across the Sahel region.”

2. Global Britain

The UK’s pivot to the Sahel is also part of the UK’s Global Britain strategy. This strategy is “about reinvesting in our relationships, championing the rules-based international order and demonstrating that the UK is open, outward-looking and confident on the world stage.” The Global Britain strategy is referenced throughout UK policy documents and public statements and is often seen as an attempt to demonstrate the UK’s global focus – especially in light of the UK’s imminent withdrawal from the EU. The pivot to the Sahel helps this strategy in two ways: it maintains international relationships (especially with European allies) and it coincides with the UK’s renewed commitment to the UN.

To the first of these, the focus on the Sahel is an important way of maintaining alliances with the UK’s (especially European) allies. For instance, the FCO has said the pivot to the Sahel will “support our alliances with international partners such as France, Germany and the [African Union] as we exit the European Union.” A number of officials we spoke to also argued that maintaining relations with France was a key driver for the UK’s renewed focus in the region; for example, one soldier in Kenya said of the pivot to the Sahel, “post-Brexit we need trade deals with France.”

Another aspect of this is supporting the UN. In September 2019, ahead of his trip to the UN General Assembly in New York, Foreign Secretary, Dominic Raab said: “As we make progress in our Brexit negotiations, we are also taking our vision of a truly Global Britain to the UN – leading by example as a force for good in the world.” The UK has exceeded its commitment to double its 2015 contribution of personnel to UN Peacekeeping operations, increasing their number from 291 to 740 by May 2018, and is now globally the sixth largest contributor financially.

There is already evidence of the UK’s commitment to the UN impacting the UK’s approach to the Sahel. For example, the UK has pledged £49.5 million to the UN mission in Mali as part of the UK’s regular contributions to UN peacekeeping missions. It is clear then that there will be a number of big changes in how the UK engages in this region of Africa. Below we set out some concrete changes that we might expect to see in the year ahead.

How?

It still remains unclear exactly what this pivot to the Sahel will look like, but it is likely to see a shift of British people and resources to the region. In the FCO’s own description of this shift, it listed a number of new funding streams, including:

£2.3 million of humanitarian aid across the region between 2015-19 (making it “the third largest humanitarian donor to the Sahel”)

£50 million to support climate change resilience

£30 million “to support education in the Sahel and neighbouring countries.”

To support these commitments, more UK personnel will be working (in the region and in Whitehall) on the Sahel. Harriet Matthews, Director for Africa at the FCO, noted that the UK Government has “expanded a joint unit on the Sahel” (a unit made up of people from different UK departments, such as the FCO, the Ministry of Defence and the Department for International Development) to oversee activity in the region.

The UK has also promised “an increased UK presence” in the Sahel. It has said that it will increase the size of UK embassies in Mali and Mauritania, open “a regional hub” in Dakar, Senegal, and establish new embassies in Niger and Chad. The FCO does not provide a specific timeline for these changes.

In one of her last acts as British Defence Secretary, in July 2019, Penny Mordaunt also announced that a long-range reconnaissance task group of 250 personnel will be deployed to Mali in 2020. These UK soldiers will be “asked to reach parts of Mali that most militaries cannot, to feed on-the-ground intelligence back to the [UN] mission headquarters.” This represents one of the biggest British peacekeeping deployments since Bosnia and it will be the most dangerous mission for British forces since Afghanistan. MINUSMA is the UN peacekeeping mission with the highest casualty rate in the world and, since its inception, 206 UN peacekeepers have been killed as part of it.

Internationally, the UK is also likely to play a greater role in conversations about the region. For instance, it is a member of the Sahel Alliance, which was set up by France, Germany and the EU to focus on increasing coordination between partners working in the region. The UK also aims to place “extra staff in Paris to work alongside the French government on the Sahel.” The UK has said that it hopes that engaging with other international partners more effectively will allow it to “drive forward progress on long-term solutions to the drivers of conflict, poverty, and instability.”

Want to know more?

This has been a brief overview of the key issues and considerations of the UK’s recent “pivot to the Sahel”, something which our team look at for its own work. You can read some more in depth pieces we have written on the pivot and what it means for UK foreign policy here:

Improving the UK offer in Africa: Lessons from military partnerships on the continent by Abigail Watson and Emily Knowles

Fusion Doctrine in Five Steps: Lessons Learned from Remote Warfare in Africa by Abigail Watson and Megan Karlshoej-Pedersen

Mali: Consequences of a War by Paul Rogers

Devils in the Detail: Implementing Mali's New Peace Accord by Richard Reeve

Security in the Sahel: Two-Part Briefing by Richard Reeve

The Military Intervention in Mali and Beyond: An Interview with Bruno Charbonneau

Libya: Between the Sahel-Sahara and the Islamic State Crises by Richard Reeve

From New Frontier to New Normal: Counter-terrorism Operations in the Sahel-Sahara by Richard Reeve and Zoë Pelter

Too Quiet on the Western Front? Counter-terrorism Build-up in the Sahel-Sahara by Richard Reeve

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

About the author

Abigail Watson is the Research Manager at ORG's Remote Warfare Programme.

UGent-leerstoel Etienne Vermeersch botst op kritiek van Fons Dewulf - Boudry hekelt optreden Thunberg

ID: 201909231142

In De Standaard verwijt Dewulf aan Vermeersch dat hij de controverse zocht.

De arme kerel heeft bijscholing nodig. Vermeersch liet vaak een ander geluid horen dan wat de orkestleiders wilden horen. Dat is niet hetzelfde als de controverse zoeken. Dat is het algemene brave discours kritisch bijsturen.

Heeft Dewulf misschien naast de leerstoel gegrepen? Die ging naar Maarten Boudry. Zowel Dewulf als Boudry bewijzen (laatstgenoemde in De Afspraak in een reactie op het optreden van Greta Thunberg in de VN) overigens dat er voorlopig geen waardig opvolger voorhanden is voor Etienne Vermeersch.

Boudry hekelde de toon van de uitspraken van Thunberg en noemde haar optreden daarom contra-productief. Dat is een veelgebruikte tactiek om de boodschap onder te sneeuwen. Bovendien is Thunberg nog maar een kind, zo stelde hij samen met rector Van Goethem vast. Ook al een goedkoop argument om niet naar de boodschap te moeten luisteren.

En de boodschap is deze:

"My message is that we'll be watching you.

"This is all wrong. I shouldn't be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you!

"You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I'm one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

"For more than 30 years, the science has been crystal clear. How dare you continue to look away and come here saying that you're doing enough, when the politics and solutions needed are still nowhere in sight.

"You say you hear us and that you understand the urgency. But no matter how sad and angry I am, I do not want to believe that. Because if you really understood the situation and still kept on failing to act, then you would be evil. And that I refuse to believe.

"The popular idea of cutting our emissions in half in 10 years only gives us a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees [Celsius], and the risk of setting off irreversible chain reactions beyond human control.

"Fifty percent may be acceptable to you. But those numbers do not include tipping points, most feedback loops, additional warming hidden by toxic air pollution or the aspects of equity and climate justice. They also rely on my generation sucking hundreds of billions of tons of your CO2 out of the air with technologies that barely exist.

"So a 50% risk is simply not acceptable to us — we who have to live with the consequences.

"To have a 67% chance of staying below a 1.5 degrees global temperature rise – the best odds given by the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] – the world had 420 gigatons of CO2 left to emit back on Jan. 1st, 2018. Today that figure is already down to less than 350 gigatons.

"How dare you pretend that this can be solved with just 'business as usual' and some technical solutions? With today's emissions levels, that remaining CO2 budget will be entirely gone within less than 8 1/2 years.

"There will not be any solutions or plans presented in line with these figures here today, because these numbers are too uncomfortable. And you are still not mature enough to tell it like it is.

"You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say: We will never forgive you.

"We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.

"Thank you."

De arme kerel heeft bijscholing nodig. Vermeersch liet vaak een ander geluid horen dan wat de orkestleiders wilden horen. Dat is niet hetzelfde als de controverse zoeken. Dat is het algemene brave discours kritisch bijsturen.

Heeft Dewulf misschien naast de leerstoel gegrepen? Die ging naar Maarten Boudry. Zowel Dewulf als Boudry bewijzen (laatstgenoemde in De Afspraak in een reactie op het optreden van Greta Thunberg in de VN) overigens dat er voorlopig geen waardig opvolger voorhanden is voor Etienne Vermeersch.

Boudry hekelde de toon van de uitspraken van Thunberg en noemde haar optreden daarom contra-productief. Dat is een veelgebruikte tactiek om de boodschap onder te sneeuwen. Bovendien is Thunberg nog maar een kind, zo stelde hij samen met rector Van Goethem vast. Ook al een goedkoop argument om niet naar de boodschap te moeten luisteren.

En de boodschap is deze:

"My message is that we'll be watching you.

"This is all wrong. I shouldn't be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you!

"You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I'm one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

"For more than 30 years, the science has been crystal clear. How dare you continue to look away and come here saying that you're doing enough, when the politics and solutions needed are still nowhere in sight.

"You say you hear us and that you understand the urgency. But no matter how sad and angry I am, I do not want to believe that. Because if you really understood the situation and still kept on failing to act, then you would be evil. And that I refuse to believe.

"The popular idea of cutting our emissions in half in 10 years only gives us a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees [Celsius], and the risk of setting off irreversible chain reactions beyond human control.

"Fifty percent may be acceptable to you. But those numbers do not include tipping points, most feedback loops, additional warming hidden by toxic air pollution or the aspects of equity and climate justice. They also rely on my generation sucking hundreds of billions of tons of your CO2 out of the air with technologies that barely exist.

"So a 50% risk is simply not acceptable to us — we who have to live with the consequences.

"To have a 67% chance of staying below a 1.5 degrees global temperature rise – the best odds given by the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] – the world had 420 gigatons of CO2 left to emit back on Jan. 1st, 2018. Today that figure is already down to less than 350 gigatons.

"How dare you pretend that this can be solved with just 'business as usual' and some technical solutions? With today's emissions levels, that remaining CO2 budget will be entirely gone within less than 8 1/2 years.

"There will not be any solutions or plans presented in line with these figures here today, because these numbers are too uncomfortable. And you are still not mature enough to tell it like it is.

"You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say: We will never forgive you.

"We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.

"Thank you."

Tracking Global Oil Refineries and their Emissions

ID: 201712291469

December 29, 2017/2 Comments/in Articles, Data and Analysis /by Ted Auch, PhD

Potential Conflict Hotspots and Global Productivity Choke Points

Today, FracTracker is releasing a complete inventory of all 536 global oil refineries, along with estimates of daily capacity, CO2 emissions per year, and various products. These data have also been visualized in the map below.

Total productivity from these refineries amounts to 79,372,612 barrels per day (BPD) of oil worldwide, according to the data we were able to compile. However, based on the International Energy Agency, global production is currently around 96 million BPD, which means that our capacity estimates are more indicative of conditions between 2002 and 2003 according to BP’s World Oil Production estimates. We estimate this disparity is a result of countries’ reluctance to share individual refinery values or rates of change due to national security concerns or related strategic reasons.

These refineries are emitting roughly 260-283 billion metric tons (BMT) of CO2[1], 1.2-1.3 BMT of methane and 46-51 million metric tons of nitrous oxide (N2O) into the atmosphere each year. The latter two compounds have climate change potentials equivalent to 28.2-30.7 BMT and 14.1-15.3 BMT CO2, respectively.

66 million

Assuming the planet’s 7.6 billion people emit 4.9-5.0 metric tons per capita of CO2 per year, emissions from these 536 refineries amounts to the CO2 emissions of 52-57 million people. If you include the facilities’ methane and N2O emissions, this figure rises to 61-66 million people equivalents every year, essentially the populations of the United Kingdom or France.

BP’s data indicate that the amount of oil being refined globally is increasing by 923,000 BPD per year (See Figure 1). This increase is primarily due to improved productivity from existing refineries. For example, BP’s own Whiting, IN refinery noted a “$4-billion revamp… to boost its intake of Canadian crude oil from 85,000 bpd to 350,000 bpd.”

Potential Hotspots and Chokepoints

Across the globe, countries and companies are beginning to make bold predictions about their ability to refine oil.

Nigeria, for example, recently claimed they would be increasing oil refining capacity by 13% from 2.4 to 2.7 million BPD. Currently, however, our data indicate Nigeria is only producing a fraction of this headline number (i.e., 445,000 BPD). The country’s estimates seem to be more indicative of conditions in Nigeria in the late 1960s when oil was first discovered in the Niger Delta. Learn more.

Is investing in – and doubling down on – oil refining capacity a smart idea for Nigeria’s people and economy, however? At this point, the country’s population is 3.5 times greater than it was in the 60’s and is growing at a remarkable rate of 2.7% per year. Yet, Nigeria’s status as one of the preeminent “Petro States” has done very little for the majority of its population – The oil industry and the Niger Delta have become synonymous with increased infant mortality and rampant oil spills.

Sadly, the probability that the situation will improve in a warming – and more politically volatile – world is not very likely.

Such a dependency on oil price has been coupled to political instability in Nigeria, prompting some to question whether the discovery of oil was a cure or a curse given that the country depends on oil prices – and associated volatility – to balance its budget: Of all the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) countries, Nigeria is near the top of the list when it comes to the price of oil the country needs to balance its budget – Deutsche Bank and IMF estimate $123 per barrel as their breaking point. This is a valuation that oil has only exceeded or approached 4.4% of the time since 1987 (See Figure 2).

Former Central Bank of Nigeria Governor, Charles Soludo, once put this reliance in context:

… For too long, we have lived with borrowed robes, and I think for the next generation, for the 400 million Nigerians expected in this country by the year 2050, oil cannot be the way forward for the future.

Other regions are also at risk from the oil market’s power and volatility. In Libya, for example, the Ras Lanuf oil refinery (with a capacity of 220,000 BPD) and the country’s primary oil export terminal in Brega were the focal point of the Libyan civil war in 2011. Not coincidentally, Libya also happens to be the Petro State that needs the highest per-barrel price for oil to balance its budget (See Figure 2). Muammar Gaddafi and the opposition, National Transitional Council, jostled for control of this pivotal choke point in the Africa-to-Europe hydrocarbon supply chain.

The fact that refineries like these – and others in similarly volatile regions of the Middle East – produce an impressive 10% (7,166,900 BPD) of global demand speaks to the fragility of these Hydrocarbon Industrial Complex focal points, as well as the planet’s fragile dependence on fossil fuels going forward.

Dividing Neighbors

These components of the fossil fuel industry, and their associated feedstocks and pipelines, will continue to divide neighbors and countries as political disenfranchisement and inequality grow, the climate continues to change, and resource limitations put increasing stress on food security and watershed resiliency worldwide.

Not surprisingly, every one of these factors places more strain on countries and weakens their ability to govern responsibly.

Thus, many observers speculate that these factors are converging to create a kind of perfect storm that forces OPEC governments and their corporate partners to lean even more heavily on their respective militaries and for-profit private military contractors (PMCs) to prevent social unrest while insuring supply chain stability and shareholder return.[2,3] The increased reliance on PMCs to provide domestic security for energy infrastructure is growing and evolving to the point where in some countries it may be hard to determine where a state’s sovereignty ends and a PMC’s dominance begins – Erik Prince’s activities in the Middle East and Africa on China’s behalf and his recent aspirations for Afghanistan are a case in point.

To paraphrase Mark Twain, whiskey is for drinking and hydrocarbons are for fighting over.

The international and regional unaccountability of PMCs has added a layer of complexity to this conversation about energy security and independence. Countries such as Saudi Arabia and Venezuela provide examples of how fragile political stability is, and more importantly how dependent this stability is on oil refinery production and what OPEC is calling ‘New Optimism.’ To be sure, PMCs are playing an increasing role in political (in)stability and energy production and transport. Since knowledge and transparency are essential for peaceful resolutions, we will continue to map and chronicle the intersections of geopolitics, energy production and transport, social justice, and climate change.

By Ted Auch, Great Lakes Program Coordinator, FracTracker Alliance; and Bryan Stinchfield, Associate Professor of Organization Studies, Department Chair of Business, Organizations & Society, Franklin & Marshall College

Relevant Data

Inventory of all 536 Global Oil Refineries: Download zip file

Inventory of all Global Oil and Gas Shale Plays: Download zip file

Footnotes and References

Assuming a tons of CO2 to barrels of oil per day ratio of 8.99 to 9.78 tons of CO2 per barrel of oil based on an analysis we’ve conducted of 146 refineries in the United States.

B. Stinchfield. 2017. “The Creeping Privatization of America’s Armed Forces”. Newsweek, May 28th, 2017, New York, NY.

R. Gray. “Erik Prince’s Plan to Privatize the War in Afghanistan”. The Atlantic, August 18th, 2017, New York, NY.

see link

geconsulteerd 20200128

Potential Conflict Hotspots and Global Productivity Choke Points

Today, FracTracker is releasing a complete inventory of all 536 global oil refineries, along with estimates of daily capacity, CO2 emissions per year, and various products. These data have also been visualized in the map below.

Total productivity from these refineries amounts to 79,372,612 barrels per day (BPD) of oil worldwide, according to the data we were able to compile. However, based on the International Energy Agency, global production is currently around 96 million BPD, which means that our capacity estimates are more indicative of conditions between 2002 and 2003 according to BP’s World Oil Production estimates. We estimate this disparity is a result of countries’ reluctance to share individual refinery values or rates of change due to national security concerns or related strategic reasons.

These refineries are emitting roughly 260-283 billion metric tons (BMT) of CO2[1], 1.2-1.3 BMT of methane and 46-51 million metric tons of nitrous oxide (N2O) into the atmosphere each year. The latter two compounds have climate change potentials equivalent to 28.2-30.7 BMT and 14.1-15.3 BMT CO2, respectively.

66 million

Assuming the planet’s 7.6 billion people emit 4.9-5.0 metric tons per capita of CO2 per year, emissions from these 536 refineries amounts to the CO2 emissions of 52-57 million people. If you include the facilities’ methane and N2O emissions, this figure rises to 61-66 million people equivalents every year, essentially the populations of the United Kingdom or France.

BP’s data indicate that the amount of oil being refined globally is increasing by 923,000 BPD per year (See Figure 1). This increase is primarily due to improved productivity from existing refineries. For example, BP’s own Whiting, IN refinery noted a “$4-billion revamp… to boost its intake of Canadian crude oil from 85,000 bpd to 350,000 bpd.”

Potential Hotspots and Chokepoints

Across the globe, countries and companies are beginning to make bold predictions about their ability to refine oil.

Nigeria, for example, recently claimed they would be increasing oil refining capacity by 13% from 2.4 to 2.7 million BPD. Currently, however, our data indicate Nigeria is only producing a fraction of this headline number (i.e., 445,000 BPD). The country’s estimates seem to be more indicative of conditions in Nigeria in the late 1960s when oil was first discovered in the Niger Delta. Learn more.

Is investing in – and doubling down on – oil refining capacity a smart idea for Nigeria’s people and economy, however? At this point, the country’s population is 3.5 times greater than it was in the 60’s and is growing at a remarkable rate of 2.7% per year. Yet, Nigeria’s status as one of the preeminent “Petro States” has done very little for the majority of its population – The oil industry and the Niger Delta have become synonymous with increased infant mortality and rampant oil spills.

Sadly, the probability that the situation will improve in a warming – and more politically volatile – world is not very likely.

Such a dependency on oil price has been coupled to political instability in Nigeria, prompting some to question whether the discovery of oil was a cure or a curse given that the country depends on oil prices – and associated volatility – to balance its budget: Of all the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) countries, Nigeria is near the top of the list when it comes to the price of oil the country needs to balance its budget – Deutsche Bank and IMF estimate $123 per barrel as their breaking point. This is a valuation that oil has only exceeded or approached 4.4% of the time since 1987 (See Figure 2).

Former Central Bank of Nigeria Governor, Charles Soludo, once put this reliance in context:

… For too long, we have lived with borrowed robes, and I think for the next generation, for the 400 million Nigerians expected in this country by the year 2050, oil cannot be the way forward for the future.

Other regions are also at risk from the oil market’s power and volatility. In Libya, for example, the Ras Lanuf oil refinery (with a capacity of 220,000 BPD) and the country’s primary oil export terminal in Brega were the focal point of the Libyan civil war in 2011. Not coincidentally, Libya also happens to be the Petro State that needs the highest per-barrel price for oil to balance its budget (See Figure 2). Muammar Gaddafi and the opposition, National Transitional Council, jostled for control of this pivotal choke point in the Africa-to-Europe hydrocarbon supply chain.

The fact that refineries like these – and others in similarly volatile regions of the Middle East – produce an impressive 10% (7,166,900 BPD) of global demand speaks to the fragility of these Hydrocarbon Industrial Complex focal points, as well as the planet’s fragile dependence on fossil fuels going forward.

Dividing Neighbors

These components of the fossil fuel industry, and their associated feedstocks and pipelines, will continue to divide neighbors and countries as political disenfranchisement and inequality grow, the climate continues to change, and resource limitations put increasing stress on food security and watershed resiliency worldwide.

Not surprisingly, every one of these factors places more strain on countries and weakens their ability to govern responsibly.

Thus, many observers speculate that these factors are converging to create a kind of perfect storm that forces OPEC governments and their corporate partners to lean even more heavily on their respective militaries and for-profit private military contractors (PMCs) to prevent social unrest while insuring supply chain stability and shareholder return.[2,3] The increased reliance on PMCs to provide domestic security for energy infrastructure is growing and evolving to the point where in some countries it may be hard to determine where a state’s sovereignty ends and a PMC’s dominance begins – Erik Prince’s activities in the Middle East and Africa on China’s behalf and his recent aspirations for Afghanistan are a case in point.

To paraphrase Mark Twain, whiskey is for drinking and hydrocarbons are for fighting over.

The international and regional unaccountability of PMCs has added a layer of complexity to this conversation about energy security and independence. Countries such as Saudi Arabia and Venezuela provide examples of how fragile political stability is, and more importantly how dependent this stability is on oil refinery production and what OPEC is calling ‘New Optimism.’ To be sure, PMCs are playing an increasing role in political (in)stability and energy production and transport. Since knowledge and transparency are essential for peaceful resolutions, we will continue to map and chronicle the intersections of geopolitics, energy production and transport, social justice, and climate change.

By Ted Auch, Great Lakes Program Coordinator, FracTracker Alliance; and Bryan Stinchfield, Associate Professor of Organization Studies, Department Chair of Business, Organizations & Society, Franklin & Marshall College

Relevant Data

Inventory of all 536 Global Oil Refineries: Download zip file

Inventory of all Global Oil and Gas Shale Plays: Download zip file

Footnotes and References

Assuming a tons of CO2 to barrels of oil per day ratio of 8.99 to 9.78 tons of CO2 per barrel of oil based on an analysis we’ve conducted of 146 refineries in the United States.

B. Stinchfield. 2017. “The Creeping Privatization of America’s Armed Forces”. Newsweek, May 28th, 2017, New York, NY.

R. Gray. “Erik Prince’s Plan to Privatize the War in Afghanistan”. The Atlantic, August 18th, 2017, New York, NY.

see link

geconsulteerd 20200128

Land: INT

NSA luisterde wereldleiders af om oliebelangen te beschermen

ID: 201602231344

Today, 23 February 2016 at 00:00 GMT, WikiLeaks publishes highly classified documents showing that the NSA bugged meetings between UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon's and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, between Israel prime minister Netanyahu and Italian prime minister Berlusconi, between key EU and Japanese trade ministers discussing their secret trade red-lines at WTO negotiations, as well as details of a private meeting between then French president Nicolas Sarkozy, Merkel and Berlusconi.

The documents also reveal the content of the meetings from Ban Ki Moon's strategising with Merkel over climate change, to Netanyahu's begging Berlusconi to help him deal with Obama, to Sarkozy telling Berlusconi that the Italian banking system would soon "pop like a cork".

Some documents are classified TOP-SECRET / COMINT-GAMMA and are the most highly classified documents ever published by a media organization.

WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange said "Today we showed that UN Secretary General Ban KiMoon's private meetings over how to save the planet from climate change were bugged by a country intent on protecting its largest oil companies. We previously published Hillary Clinton orders that US diplomats were to steal the Secretary General's DNA. The US government has signed agreements with the UN that it will not engage in such conduct against the UN--let alone its Secretary General. It will be interesting to see the UN's reaction, because if the Secretary General can be targetted without consequence then everyone from world leader to street sweeper is at risk."

The documents also reveal the content of the meetings from Ban Ki Moon's strategising with Merkel over climate change, to Netanyahu's begging Berlusconi to help him deal with Obama, to Sarkozy telling Berlusconi that the Italian banking system would soon "pop like a cork".

Some documents are classified TOP-SECRET / COMINT-GAMMA and are the most highly classified documents ever published by a media organization.

WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange said "Today we showed that UN Secretary General Ban KiMoon's private meetings over how to save the planet from climate change were bugged by a country intent on protecting its largest oil companies. We previously published Hillary Clinton orders that US diplomats were to steal the Secretary General's DNA. The US government has signed agreements with the UN that it will not engage in such conduct against the UN--let alone its Secretary General. It will be interesting to see the UN's reaction, because if the Secretary General can be targetted without consequence then everyone from world leader to street sweeper is at risk."

DR Congo: Climate of Fear - Police Operation Kills 51 Young Men and Boys

ID: 201411200404

(Kinshasa) – Police in the Democratic Republic of Congo summarily killed at least 51 youth and forcibly disappeared 33 others during an anti-crime campaign that began a year ago, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. “Operation Likofi,” which lasted from November 2013 to February 2014, targeted alleged gang members in Congo’s capital, Kinshasa.

(Kinshasa) – Police in the Democratic Republic of Congo summarily killed at least 51 youth and forcibly disappeared 33 others during an anti-crime campaign that began a year ago, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. “Operation Likofi,” which lasted from November 2013 to February 2014, targeted alleged gang members in Congo’s capital, Kinshasa.The 57-page report, “Operation Likofi: Police Killings and Enforced Disappearances in Kinshasa,” details how uniformed police, often wearing masks, dragged kuluna, or suspected gang members, from their homes at night and executed them. The police shot and killed the unarmed young men and boys outside their homes, in the open markets where they slept or worked, and in nearby fields or empty lots. Many others were taken without warrants to unknown locations and forcibly disappeared.

“Operation Likofi was a brutal police campaign that left a trail of cold-blooded murders in the Congolese capital,” said Daniel Bekele, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Fighting crime by committing crime does not build the rule of law but only reinforces a climate of fear. The Congolese authorities should investigate the killings, starting with the commander in charge of the operation, and bring to justice those responsible.”

Land: COD