Search

Search our 7.981 News Items

CATEGORIES

We found 438 books in our category 'POLITICS'

We found 19 news items

We found 438 books

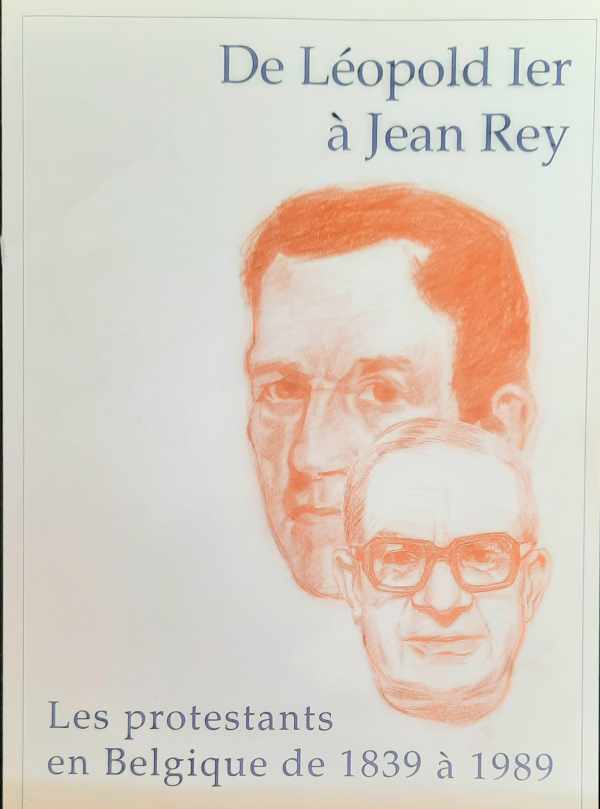

Bruxelles

Faculté universitaire de Théologie protestante

1990

BEL

condition: Goed/Bon état/Good/Gut

book number: 202307251238

De Léopold Ier à Jean Rey - Les protestants en Belgique de 1839 à 1989

Broché, in-8, pp., illustrations, notes bibliographiques, bibliographie.

@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Reinbek bei Hamburg

Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag

1968

DEU

condition: Goed/Bon état/Good/Gut

book number: 19680013

KPD-Verbot oder mit Kommunisten leben?

Pb 142 pp. Noot LT: met 'Zeittafel zur Geschichte des KPD 1918-1956'; op 17/8/1956 werd de KPD in de BRD verboden.

ABENDROTH Wolfgang @ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Antwerpen

Hautekiet

2014

condition: Very good, très bel état

book number: 202402061418

Democratieen sterven liggend - kritiek van de tactische rede

Paperback, in-8, 214 pp.

Politiek-filosofisch pleidooi voor een democratie gedragen door de gewone man.

Politiek-filosofisch pleidooi voor een democratie gedragen door de gewone man.

ABICHT Ludo@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Hoe Vlaams zijn de Vlamingen? Over identiteit.

Softcover, pb, 8vo, 137 pp.

ABICHT, BAECK, BAUER, BEHEYDT, VANDEN BERGHE, BOUCKAERT, CLAEYS, DEVREEZE, HEREMANS, MERTENS, DE MEULEMEESTER, VAN DE PERRE, PONETTE, RENSON, DE ROOVER, RUYS, SENELLE, STORME, VANHEESWIJCK, VANHEMELRYCK@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Antwerpen

De bezige bij

2013

BEL

condition: Fine

book number: 202302221420

De plicht van de dichter - Hugo Claus en de politiek

Hardcover, stofwikkel, in-8, 349 pp., illustraties

Essays en bronnenmateriaal over de rol van de politiek in leven en werk van de Vlaamse schrijver (1929-2008).

Essays en bronnenmateriaal over de rol van de politiek in leven en werk van de Vlaamse schrijver (1929-2008).

ABSILLIS Kevin@ wikipedia

€ 20.0

London

Little, Brown and Company

1995

ISR

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202404111723

Tried by Fire - The Searing True Story of Two Men at the Heart of the Struggle Between the Arabs and the Jews

Hardcover, dj, in-8, 297 pp., illustrations

Bassam Abu-Sharif, Yasser Arafat's chief lieutenant, and Uzi Mahnaimi, a former Israeli intelligence major, met in a London restaurant in 1988, and joined forces in the search for peace. Their stories, and those of their fathers and grandfathers, personify 100 years of war between Arab and Jew.

Bassam Abu-Sharif, Yasser Arafat's chief lieutenant, and Uzi Mahnaimi, a former Israeli intelligence major, met in a London restaurant in 1988, and joined forces in the search for peace. Their stories, and those of their fathers and grandfathers, personify 100 years of war between Arab and Jew.

ABU-SHARIF Basam, MAHNAIMI Uzi@ wikipedia

€ 20.0

Paris

Grasset

1999

FRA

condition: Very good

book number: 201705091813

Fort Chirac

Pb, in-8, 165 pp.

Claude Angeli (°1931) entre au Canard enchaîné en 1971, recruté par Jean Clémentin. Il devient chef des informations, puis rédacteur en chef adjoint pour l'information politique, et rédacteur en chef jusqu'en 2012.

Pour rappel:

■ Charles de Gaulle (8 janvier 1959 - 28 avril 1969)

■ Georges Pompidou (19 juin 1969 - 2 avril 1974)

■ Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (24 mai 1974 - 21 mai 1981)

■ François Mitterrand (21 mai 1981 - 17 mai 1995)

■ Jacques Chirac (17 mai 1995 - 16 mai 2007)

■ Nicolas Sarkozy (16 mai 2007 - 15 mai 2012)

■ François Hollande (15 mai 2012 - 14 mai 2017)

Claude Angeli (°1931) entre au Canard enchaîné en 1971, recruté par Jean Clémentin. Il devient chef des informations, puis rédacteur en chef adjoint pour l'information politique, et rédacteur en chef jusqu'en 2012.

Pour rappel:

■ Charles de Gaulle (8 janvier 1959 - 28 avril 1969)

■ Georges Pompidou (19 juin 1969 - 2 avril 1974)

■ Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (24 mai 1974 - 21 mai 1981)

■ François Mitterrand (21 mai 1981 - 17 mai 1995)

■ Jacques Chirac (17 mai 1995 - 16 mai 2007)

■ Nicolas Sarkozy (16 mai 2007 - 15 mai 2012)

■ François Hollande (15 mai 2012 - 14 mai 2017)

ANGELI Claude, MESNIER Stéphanie@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Mitbestimmung

Pb 158 pp.

ANTHES Jochen u.a.@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Het Belgische domdenken. Smaadschrift.

Pb, 74 pp. Een beeld van België als gemoedelijke dictatuur. De monarchie krijgt er van langs in dit smaadschrift. België is een politiek pretpark. Over de lijdzame Belg, over Wilfried Martens, over het bezoek van de paus, over België als wasautomaat voor zwart geld. Het taalgebruik van deze tedere anarchist is verfrissend poëtisch. J.A. gunt ons een blik op zijn manier om naar de dingen te kijken, bijvoorbeeld op het blijkbaar ingestudeerde handenspel tussen Boudewijn en Fabiola tijdens de kersttoespraak. Spitant, sprankelend boekje ! Als u het elders goedkoper vindt, koop het dan daar; wij scheiden er moeilijk van. Johan Anthierens (Machelen, 22 augustus 1937 — Dilbeek, 20 maart 2000) was een Vlaams journalist, columnist, publicist, schrijver, satiricus en tedere anarchist.

ANTHIERENS Johan@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Leuven

Kritak

1986

BEL

condition: Very good

book number: 202102202013

Het Belgische domdenken. Smaadschrift.

Pb, 74 pp. Een beeld van België als gemoedelijke dictatuur. De monarchie krijgt er van langs in dit smaadschrift. België is een politiek pretpark. Over de lijdzame Belg, over Wilfried Martens, over het bezoek van de paus, over België als wasautomaat voor zwart geld. Het taalgebruik van deze tedere anarchist is verfrissend poëtisch. J.A. gunt ons een blik op zijn manier om naar de dingen te kijken, bijvoorbeeld op het blijkbaar ingestudeerde handenspel tussen Boudewijn en Fabiola tijdens de kersttoespraak. Spitant, sprankelend boekje ! Als u het elders goedkoper vindt, koop het dan daar; wij scheiden er moeilijk van.

Johan Anthierens (Machelen, 22 augustus 1937 — Dilbeek, 20 maart 2000) was een Vlaams journalist, columnist, publicist, schrijver, satiricus en tedere anarchist.

Johan Anthierens (Machelen, 22 augustus 1937 — Dilbeek, 20 maart 2000) was een Vlaams journalist, columnist, publicist, schrijver, satiricus en tedere anarchist.

ANTHIERENS Johan@ wikipedia

€ 20.0

Totalitarisme (vertaling van Totalitarianism - 1951) gevolgd door Het verval van de nationale staat en het einde van de rechten van de mens (vert. van The Decline of the Nation-State and the End of the Rights of Man)

Pb, in-8, 440 pp., bibliografie, glossarium, register. Uit het Amerikaans vertaald door Remi Peeters en Dirk De Schutter. HA (1906-1975) behoort tot de belangrijkste politiek-filosofen van de 20ste eeuw. In haar boek toont zij aan dat totalitaire systemen iets anders zijn dan dictaturen: terreur is in TS tot doel op zich geworden en ideologische fictie overheerst. De voornaamste strategie van een TS zoals nazisme (1933-1945) en stalinisme (1928-1953) is het zaaien van een verlammende angst. Afwijkende visies worden niet geduld. Arendt schreef dit werk vlak na WO II. Vandaag moeten we ons durven afvragen welke regimes beantwoorden aan de omschrijvingen die HA naar voor schuift en welke rol godsdienst hierin speelt. Aanbevolen!

Pb, in-8, 440 pp., bibliografie, glossarium, register. Uit het Amerikaans vertaald door Remi Peeters en Dirk De Schutter. HA (1906-1975) behoort tot de belangrijkste politiek-filosofen van de 20ste eeuw. In haar boek toont zij aan dat totalitaire systemen iets anders zijn dan dictaturen: terreur is in TS tot doel op zich geworden en ideologische fictie overheerst. De voornaamste strategie van een TS zoals nazisme (1933-1945) en stalinisme (1928-1953) is het zaaien van een verlammende angst. Afwijkende visies worden niet geduld. Arendt schreef dit werk vlak na WO II. Vandaag moeten we ons durven afvragen welke regimes beantwoorden aan de omschrijvingen die HA naar voor schuift en welke rol godsdienst hierin speelt. Aanbevolen!Zie ook deze goede biografie:

ARENDT Hannah@ wikipedia

€ 30.0

Plaidoyer pour l'Europe décadente

Softcover, pb, 8vo, 511 pp.

ARON Raymond@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

London

William Benton

1963

GBR

condition: Very good, cover slightly damaged

book number: 40801

Encyclopaedia Britannica World Atlas. World Distributions and World Political Geography. Political-Physical Maps, Geographical Summaries, Geographical Comparisons, Glossary og Geographical Terms. Index to Political-Physical Maps.

Hardcover, leather, guilt engraving on cover and back, bound, large 4to, 518 pp, index, illstrated

ASHMORE Harry S., DODGE John V.@ wikipedia

€ 20.0

Caen

Caron

1957

FRA

condition: Goed/Bon état/Good/Gut

book number: 19570011

Le Prix de la paix

Softcover, Grand in-8 broché, 250 pp., exemplaire numéroté n° 1674. Uncut.

BABEUR Henri@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Leuven

Davidsfonds

2003

BEL

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202404151608

Onze vierkante wereldbol

Paperback, in-8, 270 pp.

Analyse van de huidige stand van zaken met betrekking tot de politiek-economische en cultureel-godsdienstige ontwikkelingen in de verschillende werelddelen, waarbij de veronderstelde hegemonie van het westen sterk wordt gerelativeerd.

Analyse van de huidige stand van zaken met betrekking tot de politiek-economische en cultureel-godsdienstige ontwikkelingen in de verschillende werelddelen, waarbij de veronderstelde hegemonie van het westen sterk wordt gerelativeerd.

BAECK Louis@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

![Book cover 202109101819: BAKOENIN Michel [BAKOUNINE Michail], WITSE Rudy (intro) | God en de Staat. De heruitgave van de brosjure](https://www.mers.be/COVERS_MERS/202109101819.jpg)

Antwerpen

de vlijtige vlieg

1968

BEL

condition: Goed/Bon état/Good/Gut

book number: 202109101819

God en de Staat. De heruitgave van de brosjure 'God en de Staat' door de russische anarchist Michel Bakoenin, verschenen in 1888 bij J.A. Fortuyn (Radicale Bibliotheek N° 1), verlucht met tekeningen van erkki liukku, pop-bedenkingen door sieg en met een inleiding van rudy witse

Polycopie, 4to, xxi + 92 pp. Met tekeningen en spotprenten. Noot LT: Rudy Witse is de schuilnaam van dichter Willem Houbrechts. De inleiding van Witse is sober van stijl en getuigt van een sterke betrokkenheid op de ideeën van Bakoenin, Proudhon en Kropotkin, voor wie hij nieuwe aandacht vraagt. Witse beklemtoont dat B. de vervormingen (excessen) van het autoritaire marxisme voorzien heeft; tenslotte benadrukt hij de voeling die B. - in tegenstelling tot de kille Marx - met de mensen zélf onderhield (zie p. xx). B. schuift volgende kerngedachte naar voor: zowel de Kerk als de Staat zijn de twee grondvesten van de slavernij der mensen (p. 54). De god, die altijd oneindig groot wordt voorgesteld, maakt de mens nietig. Idem dito voor de Staat. De kaste der wetenschappers lijkt op de priesterkaste (p. 58). B. verzet zich tegen de verering van abstracties (god, staat, vaderlandsliefde, ...) omdat die steeds weer leidt tot geweld, oorlog. Elke zingeving moet op het geluk van de mens betrokken zijn, ook de wetenschap. Een godsdienst die het hiernamaals als ultiem doel stelt, verwerpt impliciet de nood aan sociale verandering. B. spreekt over de nationale goederen (p. 85).

BAKOENIN Michel [BAKOUNINE Michail], WITSE Rudy (intro)@ wikipedia

€ 50.0

Bruxelles

G. Van Oest

1919

BEL

condition: PDF-file

book number: 19190012

Les traités de 1815 et la Belgique (e-book; PDF)

Mémoire publié pour la première fois, d'après le manuscrit original, avec un avant-propos (de juin 1919) de Pierre Nothomb. Broché In-12 IV+72 pp. Dans la série "Publications du Comité de Politique Nationale". Attention: scanned text 300 dpi in PDF-file. Note LT: Banning (12/10/1836-1898)

Mémoire publié pour la première fois, d'après le manuscrit original, avec un avant-propos (de juin 1919) de Pierre Nothomb. Broché In-12 IV+72 pp. Dans la série "Publications du Comité de Politique Nationale". Attention: scanned text 300 dpi in PDF-file. Note LT: Banning (12/10/1836-1898)Wij gebruiken WeTransfer om u deze PDF-file te zenden: simpel, snel en veilig.

Nous utilisons WeTransfer pour vous envoyer ce PDF: simple, rapide et sécurisé.

We use WeTransfer to send you this PDF-file: simple, fast and safe.

BANNING Emile@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Roma

Edizioni di Novissima

s.d.

RUS

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202405071803

Le toast de Staline

Broché, in-8, 79 pp.

BARAVELLI G.C.@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Le Livre Rouge : choix de lectures destinées à l'enseignement populaire. Exemplaire numéroté.

Softcover, 169 pp. Un des 250 exemplaires de luxe; celui-ci porte le numéro 181. Textes de Louise Ackermann, Julien Benda, Béranger, Louis Blanc, Charles de Coster, Diderot, Eschyle, Feuerbach, Gustave Flaubert, Fourier, Anatole France, Guyau, Heine, Herzen, Homère (Homerus), Victor Hugo, Jean Jaurès (lettre à un ami), Kropotkine, La Fontaine, Lamartine, Karl Marx, Louis Ménard, Michelet, Alfred de Musset, Comtesse de Noailles, Charles-Louis Philippe, Proudhon, Ernest Renan, Romain Roland, Saint-Simon, Vandervelde, Emile Verhaeren, Paul Verlaine, Charles Vildrac, Robert Wace.

BARIL Claire, VANDERVELDE Emile@ wikipedia

€ 75.0

Leuven

Global Society vzw

2014

BEL

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202206031513

Cooperaties - hoe heroveren we de economie?

Pb, 192 pp.

Pb, 192 pp.Coöperaties kunnen ons voorbij het desastreuze financieel kapitalisme en het neoliberaal roofmodel voeren.

Wij vinden dit een belangrijk boek dat de democratisering van de economie en haar sociaalecologische rol bespreekbaar wil maken. Het geeft een denkrichting aan en bewijst dat het beter is van model te veranderen dan te janken van onmacht.

Toch is de titel misleidend want hij suggereert dat 'de economie' ooit in onze handen was en dat we die kunnen 'heroveren'.

BARREZ Dirk@ wikipedia

€ 20.0

We found 19 news items

Winners of the Wolfson History Prize (GBR)

ID: 202212318971

The first awards were made in 1972. Until 1987, prizes were awarded at the end of the competition year. Since then, they have been awarded in the following year.

Until 2016, up to three awards were made every year. Since 2017, a shortlist of six titles have been announced in advance of one overall winner.

(Winners are listed alphabetically by author)

2022

Devil-Land: England Under Siege, 1588-1688

Clare Jackson

(Allen Lane)

2022 Shortlist:

The Ottomans: Khans, Caesars and Caliphs

Marc David Baer

(Basic Books)

The Ruin of all Witches: Life and Death in the New World

Malcolm Gaskill

(Allen Lane)

Going to Church in Medieval England

Nicholas Orme

(Yale University Press)

God: An Anatomy

Francesca Stavrakopoulou

(Picador)

Fallen Idols: Twelve Statues that Made History

Alex von Tunzelmann

(Headline)

2021

Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture

Sudhir Hazareesingh

(Allen Lane)

2021 Shortlist:

Survivors: Children’s Lives after the Holocaust

Rebecca Clifford

(Yale University Press)

Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe

Judith Herrin

(Allen Lane)

Double Lives: A History of Working Motherhood

Helen McCarthy

(Bloomsbury)

Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack

Richard Ovenden

(John Murray Press)

Atlantic Wars: From the Fifteenth Century to the Age of Revolution

Geoffrey Plank

(Oxford University Press)

2020

The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans

David Abulafia

(Allen Lane)

2020 Shortlist:

A History of the Bible: The Book and Its Faiths

John Barton

(Allen Lane)

A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution

Toby Green

(Allen Lane)

Cricket Country: An Indian Odyssey in the Age of Empire

Prashant Kidambi

(Oxford University Press)

The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper

Hallie Rubenhold

(Doubleday)

Chaucer: A European Life

Marion Turner

(Princeton University Press)

2019

Reckonings: Legacies of Nazi Persecution and the Quest for Justice

Mary Fulbrook

(Oxford University Press)

Shortlist:

Building Anglo-Saxon England

John Blair

(Princeton University Press)

Trading in War: London’s Maritime World in the Age of Cook and Nelson

Margarette Lincoln

(Yale University Press)

Birds in the Ancient World: Winged Words

Jeremy Mynott

(Oxford University Press)

Oscar: A Life

Matthew Sturgis

(Head of Zeus)

Empress: Queen Victoria and India

Miles Taylor

(Yale University Press)

2018

Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation

Peter Marshall

(Yale University Press)

Shortlist:

Out of China: How the Chinese Ended the Era of Western Domination

Robert Bickers

(Allen Lane)

The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine

Lindsey Fitzharris

(Allen Lane)

A Deadly Legacy: German Jews and the Great War

Tim Grady

(Yale University Press)

Black Tudors: The Untold Story

Miranda Kaufmann

(Oneworld)

Heligoland: Britain, Germany and the Struggle for the North Sea

Jan Rüger

(Oxford University Press)

2017

Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts

Christopher de Hamel

(Allen Lane)

Shortlist:

The House of the Dead: Siberian Exile under the Tsars

Daniel Beer

(Allen Lane)

Henry IV

Chris Given-Wilson

(Yale University Press)

Sleep in Early Modern England

Sasha Handley

(Yale University Press)

Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet

Lyndal Roper

(The Bodley Head)

Henry the Young King, 1155 – 1183

Matthew Strickland

(Yale University Press)

2016

Augustine: Conversions and Confessions

Robin Lane Fox

(Allen Lane)

KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Nikolaus Wachsmann

(Little, Brown)

2015

National Service: Conscription in Britain, 1945-1963

Richard Vinen

(Allen Lane)

Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914-1918

Alexander Watson

(Allen Lane)

2014

The Making of the Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning to the Emergence of the Classical World

Cyprian Broodbank

(Thames & Hudson)

Red Fortress: The Secret Heart of Russia’s History

Catherine Merridale

(Allen Lane)

2013

Thomas Wyatt: The Heart’s Forest

Susan Brigden

(Faber & Faber)

Fascist Voices: An Intimate History of Mussolini’s Italy

Christopher Duggan

(Random House)

2012

Nikolaus Pevsner: The Life

Susie Harries

(Chatto & Windus)

The Reformation of the Landscape: Religion, Identity & Memory in Early Modern Britain & Ireland

Alexandra Walsham

(Oxford University Press)

2011

The Man on Devil’s Island: Alfred Dreyfus and the Affair that Divided France

Ruth Harris

(Allen Lane)

Islanders: The Pacific in the Age of Empire

Nicholas Thomas

(Yale University Press)

2010

Russia against Napoleon: The Battle for Europe 1807 to 1814

Dominic Lieven

(Allen Lane)

The Hundred Years War, vol. III: Divided Houses

Jonathan Sumption

(Faber & Faber)

2009

Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town

Mary Beard

(Profile Books)

Dance in the Renaissance: European Fashion, French Obsession

Margaret McGowan

(Yale University Press)

2008

After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire since 1405

John Darwin

(Allen Lane)

God’s Architect: Pugin & the Building of Romantic Britain

Rosemary Hill

(Allen Lane)

2007

Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947

Christopher Clark

(Allen Lane)

City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London

Vic Gatrell

(Atlantic Books)

The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy

Adam Tooze

(Allen Lane)

2006

Shopping in the Renaissance: Consumer Cultures in Italy 1400-1600

Evelyn Welch

(Yale University Press)

Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean 400-800

Christopher Wickham

(Oxford University Press)

2005

The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia

Richard Overy

(Allen Lane)

In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War

David Reynolds

(Allen Lane)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Christopher Bayly

2004

Transformations of Love: The Friendship of John Evelyn and Margaret Godolphin

Frances Harris

(Oxford University Press)

The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940

Julian Jackson

(Oxford University Press)

Reformation: Europe’s House Divided 1490-1700

Diarmaid MacCulloch

(Allen Lane)

2003

White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India

William Dalrymple

(HarperCollins)

Marianne in Chains: In search of the German Occupation 1940-1945

Robert Gildea

(Macmillan)

2002

Facing the Ocean: The Atlantic and its Peoples 8000BC-AD1500

Barry Cunliffe

(Oxford University Press)

London in the Twentieth Century: A City and its People

Jerry White

(Viking)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history:

Roy Jenkins

2001

Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis

Ian Kershaw

(Allen Lane)

The Balkans: From the End of Byzantium to the Present Day

Mark Mazower

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World

Roy Porter

(Allen Lane)

2000

An Intimate History of Killing: Face-To-Face Killing In Twentieth-Century Warfare

Joanna Bourke

(Granta Books)

Salisbury: Victorian Titan

Andrew Roberts

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Asa Briggs

1999

Stalingrad

Antony Beevor

(Viking)

The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England

Amanda Vickery

(Yale University Press)

1998

The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century

John Brewer

(HarperCollins)

Jennie Lee: A Life

Patricia Hollis

(Oxford University Press)

1997

A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924

Orlando Figes

(Jonathan Cape)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Eric Hobsbawm

1996

Gladstone, 1875-1898

HCG Matthew

(Oxford University Press)

1995

William Morris: A Life for Our Time

Fiona MacCarthy

(Faber & Faber)

The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany

John Röhl

(Cambridge University Press)

1994

The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change 950-1350

Robert Bartlett

(Allen Lane)

Living and Dying in England 1100-1540: The Monastic Experience

Barbara Harvey

(Oxford University Press)

1993

Britons: Forging the Nation 1707 – 1837

Linda Colley

(Yale University Press)

John Maynard Keynes, vol. 2: the Economist as Saviour 1920-1937

Robert Skidelsky

(PanMacmillan)

1992

Giordano Bruno and the Embassy Affair

John Bossy

(Yale University Press)

Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives

Alan Bullock

(HarperCollins)

1991

The Architecture of Medieval Britain: A Social History

Colin Platt

(Yale University Press)

1990

The Quest for El Cid

Richard Fletcher

(Hutchinson)

How War Came

Donald Cameron Watt

(William Heinemann)

1989

Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years, 1830-1910

Richard Evans

(Oxford University Press)

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Control from 1500-2000

Paul Kennedy

(Unwin Hyman)

1987

Conquest, Coexistence, and Change: Wales 1063-1415

Rees Davies

(Oxford University Press)

The Mediterranean Passion: Victorians and Edwardians in the South

John Pemble

(Oxford University Press)

1986

The Count-Duke of Olivares: The Statesman in an Age of Decline

John Elliott

(Yale University Press)

European Jewry in the Age of Mercantilism 1550-1750

Jonathan Israel

(Oxford University Press)

1985

Dudley Docker: The Life and Times of a Trade Warrior

Richard Davenport-Hines

(Cambridge University Press)

Lloyd George: From Peace to War, 1912-1916

John Grigg

(Methuen)

1984

The Weaker Vessel: Woman’s Lot in Seventeenth-Century England

Antonia Fraser

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Chivalry

Maurice Keen

(Yale University Press)

1983

Winston S. Churchill, vol. VI: Finest Hour

Martin Gilbert

(Heinemann)

King George V

Kenneth Rose

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

1982

Death and the Enlightenment: Changing Attitudes to Death Among Christians and Unbelievers in Eighteenth-century France

John McManners

(Oxford University Press)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Steven Runciman

1981

A Liberal Descent: Victorian Historians and the English Past

John Burrow

(Cambridge University Press)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Owen Chadwick

1980

The Making of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1550-1700: An Interpretation

Robert Evans

(Oxford University Press)

Culture and Anarchy in Ireland, 1890-1939

FSL Lyons

(Oxford University Press)

1979

Death in Paris , 1795-1801

Richard Cobb

(Oxford University Press)

Clementine Churchill

Mary Soames

(Cassell)

The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, vol. 1: The Renaissance

Quentin Skinner

(Cambridge University Press)

1978

A Savage War of Peace: Algeria, 1954-1962

Alistair Horne

(Macmillan)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Howard Colvin

1977

Patriots and Liberators: Revolution in the Netherlands, 1780-1813

Simon Schama

(Collins)

Mussolini’s Roman Empire

Denis Mack Smith

(Longman & Co)

1976

A History of Building Types

Nikolaus Pevsner

(Thames & Hudson)

The Eastern Front 1914-17

Norman Stone

(Hodder & Stoughton)

1975

Edward VIII

Frances Donaldson

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

The Poor of Eighteenth-Century France, 1750-1789

Olwen Hufton

(Oxford University Press)

1974

The Ancient Economy

Moses Finley

(Chatto & Windus)

France, 1848-1945: Ambition, Love & Politics

Theodore Zeldin

(Oxford University Press)

1973

Henry II

WL Warren

(Eyre & Spottiswoode)

The Rosicrucian Enlightenment

Frances Yates

(Routledge & Kegan Paul)

1972

Grand Strategy, vol. IV: August 1942 – September 1943

Michael Howard

(HMSO)

Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century England

Keith Thomas

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Until 2016, up to three awards were made every year. Since 2017, a shortlist of six titles have been announced in advance of one overall winner.

(Winners are listed alphabetically by author)

2022

Devil-Land: England Under Siege, 1588-1688

Clare Jackson

(Allen Lane)

2022 Shortlist:

The Ottomans: Khans, Caesars and Caliphs

Marc David Baer

(Basic Books)

The Ruin of all Witches: Life and Death in the New World

Malcolm Gaskill

(Allen Lane)

Going to Church in Medieval England

Nicholas Orme

(Yale University Press)

God: An Anatomy

Francesca Stavrakopoulou

(Picador)

Fallen Idols: Twelve Statues that Made History

Alex von Tunzelmann

(Headline)

2021

Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture

Sudhir Hazareesingh

(Allen Lane)

2021 Shortlist:

Survivors: Children’s Lives after the Holocaust

Rebecca Clifford

(Yale University Press)

Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe

Judith Herrin

(Allen Lane)

Double Lives: A History of Working Motherhood

Helen McCarthy

(Bloomsbury)

Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack

Richard Ovenden

(John Murray Press)

Atlantic Wars: From the Fifteenth Century to the Age of Revolution

Geoffrey Plank

(Oxford University Press)

2020

The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans

David Abulafia

(Allen Lane)

2020 Shortlist:

A History of the Bible: The Book and Its Faiths

John Barton

(Allen Lane)

A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution

Toby Green

(Allen Lane)

Cricket Country: An Indian Odyssey in the Age of Empire

Prashant Kidambi

(Oxford University Press)

The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper

Hallie Rubenhold

(Doubleday)

Chaucer: A European Life

Marion Turner

(Princeton University Press)

2019

Reckonings: Legacies of Nazi Persecution and the Quest for Justice

Mary Fulbrook

(Oxford University Press)

Shortlist:

Building Anglo-Saxon England

John Blair

(Princeton University Press)

Trading in War: London’s Maritime World in the Age of Cook and Nelson

Margarette Lincoln

(Yale University Press)

Birds in the Ancient World: Winged Words

Jeremy Mynott

(Oxford University Press)

Oscar: A Life

Matthew Sturgis

(Head of Zeus)

Empress: Queen Victoria and India

Miles Taylor

(Yale University Press)

2018

Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation

Peter Marshall

(Yale University Press)

Shortlist:

Out of China: How the Chinese Ended the Era of Western Domination

Robert Bickers

(Allen Lane)

The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine

Lindsey Fitzharris

(Allen Lane)

A Deadly Legacy: German Jews and the Great War

Tim Grady

(Yale University Press)

Black Tudors: The Untold Story

Miranda Kaufmann

(Oneworld)

Heligoland: Britain, Germany and the Struggle for the North Sea

Jan Rüger

(Oxford University Press)

2017

Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts

Christopher de Hamel

(Allen Lane)

Shortlist:

The House of the Dead: Siberian Exile under the Tsars

Daniel Beer

(Allen Lane)

Henry IV

Chris Given-Wilson

(Yale University Press)

Sleep in Early Modern England

Sasha Handley

(Yale University Press)

Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet

Lyndal Roper

(The Bodley Head)

Henry the Young King, 1155 – 1183

Matthew Strickland

(Yale University Press)

2016

Augustine: Conversions and Confessions

Robin Lane Fox

(Allen Lane)

KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Nikolaus Wachsmann

(Little, Brown)

2015

National Service: Conscription in Britain, 1945-1963

Richard Vinen

(Allen Lane)

Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914-1918

Alexander Watson

(Allen Lane)

2014

The Making of the Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning to the Emergence of the Classical World

Cyprian Broodbank

(Thames & Hudson)

Red Fortress: The Secret Heart of Russia’s History

Catherine Merridale

(Allen Lane)

2013

Thomas Wyatt: The Heart’s Forest

Susan Brigden

(Faber & Faber)

Fascist Voices: An Intimate History of Mussolini’s Italy

Christopher Duggan

(Random House)

2012

Nikolaus Pevsner: The Life

Susie Harries

(Chatto & Windus)

The Reformation of the Landscape: Religion, Identity & Memory in Early Modern Britain & Ireland

Alexandra Walsham

(Oxford University Press)

2011

The Man on Devil’s Island: Alfred Dreyfus and the Affair that Divided France

Ruth Harris

(Allen Lane)

Islanders: The Pacific in the Age of Empire

Nicholas Thomas

(Yale University Press)

2010

Russia against Napoleon: The Battle for Europe 1807 to 1814

Dominic Lieven

(Allen Lane)

The Hundred Years War, vol. III: Divided Houses

Jonathan Sumption

(Faber & Faber)

2009

Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town

Mary Beard

(Profile Books)

Dance in the Renaissance: European Fashion, French Obsession

Margaret McGowan

(Yale University Press)

2008

After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire since 1405

John Darwin

(Allen Lane)

God’s Architect: Pugin & the Building of Romantic Britain

Rosemary Hill

(Allen Lane)

2007

Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947

Christopher Clark

(Allen Lane)

City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London

Vic Gatrell

(Atlantic Books)

The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy

Adam Tooze

(Allen Lane)

2006

Shopping in the Renaissance: Consumer Cultures in Italy 1400-1600

Evelyn Welch

(Yale University Press)

Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean 400-800

Christopher Wickham

(Oxford University Press)

2005

The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia

Richard Overy

(Allen Lane)

In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War

David Reynolds

(Allen Lane)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Christopher Bayly

2004

Transformations of Love: The Friendship of John Evelyn and Margaret Godolphin

Frances Harris

(Oxford University Press)

The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940

Julian Jackson

(Oxford University Press)

Reformation: Europe’s House Divided 1490-1700

Diarmaid MacCulloch

(Allen Lane)

2003

White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India

William Dalrymple

(HarperCollins)

Marianne in Chains: In search of the German Occupation 1940-1945

Robert Gildea

(Macmillan)

2002

Facing the Ocean: The Atlantic and its Peoples 8000BC-AD1500

Barry Cunliffe

(Oxford University Press)

London in the Twentieth Century: A City and its People

Jerry White

(Viking)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history:

Roy Jenkins

2001

Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis

Ian Kershaw

(Allen Lane)

The Balkans: From the End of Byzantium to the Present Day

Mark Mazower

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World

Roy Porter

(Allen Lane)

2000

An Intimate History of Killing: Face-To-Face Killing In Twentieth-Century Warfare

Joanna Bourke

(Granta Books)

Salisbury: Victorian Titan

Andrew Roberts

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Asa Briggs

1999

Stalingrad

Antony Beevor

(Viking)

The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England

Amanda Vickery

(Yale University Press)

1998

The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century

John Brewer

(HarperCollins)

Jennie Lee: A Life

Patricia Hollis

(Oxford University Press)

1997

A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924

Orlando Figes

(Jonathan Cape)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Eric Hobsbawm

1996

Gladstone, 1875-1898

HCG Matthew

(Oxford University Press)

1995

William Morris: A Life for Our Time

Fiona MacCarthy

(Faber & Faber)

The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany

John Röhl

(Cambridge University Press)

1994

The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change 950-1350

Robert Bartlett

(Allen Lane)

Living and Dying in England 1100-1540: The Monastic Experience

Barbara Harvey

(Oxford University Press)

1993

Britons: Forging the Nation 1707 – 1837

Linda Colley

(Yale University Press)

John Maynard Keynes, vol. 2: the Economist as Saviour 1920-1937

Robert Skidelsky

(PanMacmillan)

1992

Giordano Bruno and the Embassy Affair

John Bossy

(Yale University Press)

Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives

Alan Bullock

(HarperCollins)

1991

The Architecture of Medieval Britain: A Social History

Colin Platt

(Yale University Press)

1990

The Quest for El Cid

Richard Fletcher

(Hutchinson)

How War Came

Donald Cameron Watt

(William Heinemann)

1989

Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years, 1830-1910

Richard Evans

(Oxford University Press)

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Control from 1500-2000

Paul Kennedy

(Unwin Hyman)

1987

Conquest, Coexistence, and Change: Wales 1063-1415

Rees Davies

(Oxford University Press)

The Mediterranean Passion: Victorians and Edwardians in the South

John Pemble

(Oxford University Press)

1986

The Count-Duke of Olivares: The Statesman in an Age of Decline

John Elliott

(Yale University Press)

European Jewry in the Age of Mercantilism 1550-1750

Jonathan Israel

(Oxford University Press)

1985

Dudley Docker: The Life and Times of a Trade Warrior

Richard Davenport-Hines

(Cambridge University Press)

Lloyd George: From Peace to War, 1912-1916

John Grigg

(Methuen)

1984

The Weaker Vessel: Woman’s Lot in Seventeenth-Century England

Antonia Fraser

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Chivalry

Maurice Keen

(Yale University Press)

1983

Winston S. Churchill, vol. VI: Finest Hour

Martin Gilbert

(Heinemann)

King George V

Kenneth Rose

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

1982

Death and the Enlightenment: Changing Attitudes to Death Among Christians and Unbelievers in Eighteenth-century France

John McManners

(Oxford University Press)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Steven Runciman

1981

A Liberal Descent: Victorian Historians and the English Past

John Burrow

(Cambridge University Press)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Owen Chadwick

1980

The Making of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1550-1700: An Interpretation

Robert Evans

(Oxford University Press)

Culture and Anarchy in Ireland, 1890-1939

FSL Lyons

(Oxford University Press)

1979

Death in Paris , 1795-1801

Richard Cobb

(Oxford University Press)

Clementine Churchill

Mary Soames

(Cassell)

The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, vol. 1: The Renaissance

Quentin Skinner

(Cambridge University Press)

1978

A Savage War of Peace: Algeria, 1954-1962

Alistair Horne

(Macmillan)

For distinguished contribution to the writing of history

Howard Colvin

1977

Patriots and Liberators: Revolution in the Netherlands, 1780-1813

Simon Schama

(Collins)

Mussolini’s Roman Empire

Denis Mack Smith

(Longman & Co)

1976

A History of Building Types

Nikolaus Pevsner

(Thames & Hudson)

The Eastern Front 1914-17

Norman Stone

(Hodder & Stoughton)

1975

Edward VIII

Frances Donaldson

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

The Poor of Eighteenth-Century France, 1750-1789

Olwen Hufton

(Oxford University Press)

1974

The Ancient Economy

Moses Finley

(Chatto & Windus)

France, 1848-1945: Ambition, Love & Politics

Theodore Zeldin

(Oxford University Press)

1973

Henry II

WL Warren

(Eyre & Spottiswoode)

The Rosicrucian Enlightenment

Frances Yates

(Routledge & Kegan Paul)

1972

Grand Strategy, vol. IV: August 1942 – September 1943

Michael Howard

(HMSO)

Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century England

Keith Thomas

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Land: GBR

The Corruption Perceptions Index 2019 published - Belgium 17th best - Bad score of Turkey not commented in the report - RDC Congo at place 168 in the ranking

ID: 202001247812

The Corruption Perceptions Index 2019 reveals a staggering number of countries are showing little to no improvement in tackling corruption. Our analysis also suggests that reducing big money in politics and promoting inclusive political decision-making are essential to curb corruption. The CPI scores 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, according to experts and business people.

The Corruption Perceptions Index 2019 reveals a staggering number of countries are showing little to no improvement in tackling corruption. Our analysis also suggests that reducing big money in politics and promoting inclusive political decision-making are essential to curb corruption. The CPI scores 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, according to experts and business people.In the last year, anti-corruption movements across the globe gained momentum as millions of people joined together to speak out against corruption in their governments. Protests from Latin America, North Africa and Eastern Europe to the Middle East and Central Asia made headlines as citizens marched in Santiago, Prague, Beirut, and a host of other cities to voice their frustrations in the streets. From fraud that occurs at the highest levels of government to petty bribery that blocks access to basic public services like health care and education, citizens are fed up with corrupt leaders and institutions. This frustration fuels a growing lack of trust in government and further erodes public confidence in political leaders, elected officials and democracy. The current state of corruption speaks to a need for greater political integrity in many countries. To have any chance of curbing corruption, governments must strengthen checks and balances, limit the influence of big money in politics and ensure broad input in political decision-making. Public policies and resources should not be determined by economic power or political influence, but by fair consultation and impartial budget allocation.

Land: INT

Categorie: POLITICS - GESJOEMEL

UGent-leerstoel Etienne Vermeersch botst op kritiek van Fons Dewulf - Boudry hekelt optreden Thunberg

ID: 201909231142

In De Standaard verwijt Dewulf aan Vermeersch dat hij de controverse zocht.

De arme kerel heeft bijscholing nodig. Vermeersch liet vaak een ander geluid horen dan wat de orkestleiders wilden horen. Dat is niet hetzelfde als de controverse zoeken. Dat is het algemene brave discours kritisch bijsturen.

Heeft Dewulf misschien naast de leerstoel gegrepen? Die ging naar Maarten Boudry. Zowel Dewulf als Boudry bewijzen (laatstgenoemde in De Afspraak in een reactie op het optreden van Greta Thunberg in de VN) overigens dat er voorlopig geen waardig opvolger voorhanden is voor Etienne Vermeersch.

Boudry hekelde de toon van de uitspraken van Thunberg en noemde haar optreden daarom contra-productief. Dat is een veelgebruikte tactiek om de boodschap onder te sneeuwen. Bovendien is Thunberg nog maar een kind, zo stelde hij samen met rector Van Goethem vast. Ook al een goedkoop argument om niet naar de boodschap te moeten luisteren.

En de boodschap is deze:

"My message is that we'll be watching you.

"This is all wrong. I shouldn't be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you!

"You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I'm one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

"For more than 30 years, the science has been crystal clear. How dare you continue to look away and come here saying that you're doing enough, when the politics and solutions needed are still nowhere in sight.

"You say you hear us and that you understand the urgency. But no matter how sad and angry I am, I do not want to believe that. Because if you really understood the situation and still kept on failing to act, then you would be evil. And that I refuse to believe.

"The popular idea of cutting our emissions in half in 10 years only gives us a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees [Celsius], and the risk of setting off irreversible chain reactions beyond human control.

"Fifty percent may be acceptable to you. But those numbers do not include tipping points, most feedback loops, additional warming hidden by toxic air pollution or the aspects of equity and climate justice. They also rely on my generation sucking hundreds of billions of tons of your CO2 out of the air with technologies that barely exist.

"So a 50% risk is simply not acceptable to us — we who have to live with the consequences.

"To have a 67% chance of staying below a 1.5 degrees global temperature rise – the best odds given by the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] – the world had 420 gigatons of CO2 left to emit back on Jan. 1st, 2018. Today that figure is already down to less than 350 gigatons.

"How dare you pretend that this can be solved with just 'business as usual' and some technical solutions? With today's emissions levels, that remaining CO2 budget will be entirely gone within less than 8 1/2 years.

"There will not be any solutions or plans presented in line with these figures here today, because these numbers are too uncomfortable. And you are still not mature enough to tell it like it is.

"You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say: We will never forgive you.

"We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.

"Thank you."

De arme kerel heeft bijscholing nodig. Vermeersch liet vaak een ander geluid horen dan wat de orkestleiders wilden horen. Dat is niet hetzelfde als de controverse zoeken. Dat is het algemene brave discours kritisch bijsturen.

Heeft Dewulf misschien naast de leerstoel gegrepen? Die ging naar Maarten Boudry. Zowel Dewulf als Boudry bewijzen (laatstgenoemde in De Afspraak in een reactie op het optreden van Greta Thunberg in de VN) overigens dat er voorlopig geen waardig opvolger voorhanden is voor Etienne Vermeersch.

Boudry hekelde de toon van de uitspraken van Thunberg en noemde haar optreden daarom contra-productief. Dat is een veelgebruikte tactiek om de boodschap onder te sneeuwen. Bovendien is Thunberg nog maar een kind, zo stelde hij samen met rector Van Goethem vast. Ook al een goedkoop argument om niet naar de boodschap te moeten luisteren.

En de boodschap is deze:

"My message is that we'll be watching you.

"This is all wrong. I shouldn't be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean. Yet you all come to us young people for hope. How dare you!

"You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I'm one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

"For more than 30 years, the science has been crystal clear. How dare you continue to look away and come here saying that you're doing enough, when the politics and solutions needed are still nowhere in sight.

"You say you hear us and that you understand the urgency. But no matter how sad and angry I am, I do not want to believe that. Because if you really understood the situation and still kept on failing to act, then you would be evil. And that I refuse to believe.

"The popular idea of cutting our emissions in half in 10 years only gives us a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees [Celsius], and the risk of setting off irreversible chain reactions beyond human control.

"Fifty percent may be acceptable to you. But those numbers do not include tipping points, most feedback loops, additional warming hidden by toxic air pollution or the aspects of equity and climate justice. They also rely on my generation sucking hundreds of billions of tons of your CO2 out of the air with technologies that barely exist.

"So a 50% risk is simply not acceptable to us — we who have to live with the consequences.

"To have a 67% chance of staying below a 1.5 degrees global temperature rise – the best odds given by the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] – the world had 420 gigatons of CO2 left to emit back on Jan. 1st, 2018. Today that figure is already down to less than 350 gigatons.

"How dare you pretend that this can be solved with just 'business as usual' and some technical solutions? With today's emissions levels, that remaining CO2 budget will be entirely gone within less than 8 1/2 years.

"There will not be any solutions or plans presented in line with these figures here today, because these numbers are too uncomfortable. And you are still not mature enough to tell it like it is.

"You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say: We will never forgive you.

"We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.

"Thank you."

Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds

ID: 201510220137

Hardcover. "Drawing on its unique geography, history, and politics, this study of Turkey considers its prospects for democratic rule and its place among nations in the 21st century. Kinzer travels across the land, interviews its many peoples, and considers the key issues confronting Turkey: the role of its military; the secular and religious traditions; and the politics and human rights issues in relation to joining the European Union. Arguing that Turkey is the most "audacious nation of the twenty-first century" the author explores the unrealized potential of this nation--once the seat of a great empire--sandwiched neatly between Europe and Asia. Offers an intimate report on Turkey today, pulling aside the veil that has hidden it from the outside world. Traces its development into a modern state, and outlines the great dilemmas it now faces.Turkey is poised between Europe and Asia, caught between the glories of its Ottoman past and its hopes for a democratic future, between the traditional power of its army and the needs of its impatient citizens, between Muslim traditions and secular expectations. " 252p. index.

Hardcover. "Drawing on its unique geography, history, and politics, this study of Turkey considers its prospects for democratic rule and its place among nations in the 21st century. Kinzer travels across the land, interviews its many peoples, and considers the key issues confronting Turkey: the role of its military; the secular and religious traditions; and the politics and human rights issues in relation to joining the European Union. Arguing that Turkey is the most "audacious nation of the twenty-first century" the author explores the unrealized potential of this nation--once the seat of a great empire--sandwiched neatly between Europe and Asia. Offers an intimate report on Turkey today, pulling aside the veil that has hidden it from the outside world. Traces its development into a modern state, and outlines the great dilemmas it now faces.Turkey is poised between Europe and Asia, caught between the glories of its Ottoman past and its hopes for a democratic future, between the traditional power of its army and the needs of its impatient citizens, between Muslim traditions and secular expectations. " 252p. index.

Land: TUR

Back to the land

ID: 201412271246

The Most Reverend Dr. Thomas Nulty or Thomas McNulty (1818-1898) was born to a farming family in Fennor, Oldcastle, Co. Meath,[1][2] on July 7, 1818 and died in office as the Irish Roman Catholic Bishop of Meath[3] on Christmas Eve, 1898. Nulty was educated at Gilson School, Oldcastle, County Meath, St. Finians, Navan Seminary and Maynooth College. He was ordained in 1846. Nulty was a cleric during the Irish Potato Famine. During the course of his first pastoral appointment, he officiated at an average 11 funerals of famine victims (most children or the aged) a day, and in 1848 he described a large-scale eviction of 700 tenants in the diocese.[4]

Nulty rose to become the Most Reverend Bishop of Meath and was known as a fierce defender of the tenant rights of Irish tenant farmers throughout the 34 years that he served in that office from 1864 to 1898.[5][6] Thomas Nulty is famed for his 1881 tract Back to the Land, wherein he makes the case for land reform of the Irish land tenure system.[7] Nulty was a friend and supporter of the Irish nationalist Charles Stewart Parnell until Parnell's divorce crisis in 1889.[8][9]

Dr. Thomas Nulty, who had attended the First Vatican Council in 1870, said his last mass on December 21, 1898.

To the Clergy and Laity of the Diocese of Meath:

Dearly Beloved Brethren,-

I venture to take the liberty of dedicating the following Essay to you, as a mark of my respect and affection. In this Essay I do not, of course, address myself to you as your Bishop, for I have no divine commission to enlighten you on your civil rights, or to instruct you in the principles of Land Tenure or Political Economy. I feel, however, a deep concern even in your temporal interests — deeper, indeed, than in my own; for what temporal interests can I have save those I must always feel in your welfare? It is, then, because the Land Question is one not merely of vital importance, but one of life and death to you, as well as to the majority of my countrymen, that I have ventured to write on it at all.

With a due sense of my responsibility, I have examined this great question with all the care and consideration I had time to bestow on it. A subject so abstruse and so difficult could not, by any possibility, be made attractive and interesting. My only great regret, then, is that my numerous duties in nearly every part of the Diocese for the last month have not left me sufficient time to put my views before you with the perspicuity, the order and the persuasiveness that I should desire. However, even in the crude, unfinished form in which this Essay is now submitted to you, I hope it will prove of some use in assisting you to form a correct estimate of the real value and merit of Mr. Gladstone’s coming Bill.

For my own part, I confess I am not very sanguine in my expectations of this Bill — at any rate, when it shall have passed the Lords. The hereditary legislators will, I fear, never surrender the monopoly in the land which they have usurped for centuries past; at least till it has become quite plain to them that they have lost the power of holding it any longer. It is, however, now quite manifest to all the world — except, perhaps, to themselves — that they hold that power no longer.

We, however, can afford calmly to wait. While we are, therefore, prepared to receive with gratitude any settlement of the question which will substantially secure to us our just rights, we will never be satisfied with less. Nothing short of a full and comprehensive measure of justice will ever satisfy the tenant farmers of Ireland, or put an end to the Land League agitation.

The people of Ireland are now keenly alive to the important fact that if they are loyal and true to themselves, and that they set their faces against every form of violence and crime, they have the power to compel the landlords to surrender all their just rights in their entirety.

If the tenant farmers refuse to pay more than a just rent for their farms, and no one takes a farm from which a tenant has been evicted for the non-payment of an unjust or exorbitant rent, then our cause is practically gained. The landlords may, no doubt, wreak their vengeance on a few, whom they may regard as the leaders of the movement; but the patriotism and generosity of their countrymen will compensate these abundantly for their losses, and superabundantly reward them for the essential and important services they have rendered to their country at the critical period of its history.

You know but too well, and perhaps to your cost, that there are bad landlords in Meath, and worse still in Westmeath, and perhaps also in the other Counties of this Diocese. We are, unfortunately, too familiar with all forms of extermination, from the eviction of a Parish Priest, who was willing to pay his rent, to the wholesale clearance of the honest, industrious people of an entire district. But we have, thank God, a few good landlords, too. Some of these, like the Earl of Fingal, belong to our own faith; some, like the late Lord Athlumny, are Protestants; and some among the very best are Tories of the highest type of conservatism.

You have always cherished feelings of the deepest gratitude and affection for every landlord, irrespective of his politics or his creed, who treated you with justice, consideration and kindness. I have always heartily commended you for these feelings.

For my own part, I can assure you, I entertain no unfriendly feelings for any landlord living, and in this Essay I write of them not as individuals, but as a class, and further, I freely admit that there are individual landlords who are highly honourable exceptions to the class to which they belong. But that I heartily dislike the existing system of Land Tenure, and the frightful extent to which it has been abused, by the vast majority of landlords, will be evident to anyone who reads this Essay through.

I remain, Dearly Beloved Brethren, respectfully yours,

+THOMAS NULTY.

BACK TO THE LAND

Our Land System Not justified by its General Acceptance.

Anyone who ventures to question the justice or the policy of maintaining the present system of Irish Land Tenure will be met at once by a pretty general feeling which will warn him emphatically that its venerable antiquity entitles it, if not to reverence and respect, at least to tenderness and forbearance.

I freely admit that feeling to be most natural and perhaps very general also; but I altogether deny its reasonableness. It proves too much. Any existing social institution is undoubtedly entitled to justice and fair play; but no institution, no matter what may have been its standing or its popularity, is entitled to exceptional tenderness and forbearance if it can be shown that it is intrinsically unjust and cruel. Worse institutions by far than any system of Land Tenure can and have had a long and prosperous career, till their true character became generally known and then they were suffered to exist no longer.

Human Slavery Once Generally Accepted.

Slavery is found to have existed, as a social institution, in almost all nations, civilised as well as barbarous, and in every age of the world, up almost to our own times. We hardly ever find it in the state of a merely passing phenomenon, or as a purely temporary result of conquest or of war, but always as a settled, established and recognised state of social existence, in which generation followed generation in unbroken succession, and in which thousands upon thousands of human beings lived and died. Hardly anyone had the public spirit to question its character or to denounce its excesses; it had no struggle to make for its existence, and the degradation in which it held its unhappy victims was universally regarded as nothing worse than a mere sentimental grievance.

On the other hand, the justice of the right of property which a master claimed in his slaves was universally accepted in the light of a first principle of morality. His slaves were either born on his estate, and he had to submit to the labour and the cost of rearing and maintaining them to manhood, or he acquired them by inheritance or by free gift, or, failing these, he acquired them by the right of purchase — having paid in exchange for them what, according to the usages of society and the common estimation of his countrymen, was regarded as their full pecuniary value. Property, therefore, in slaves was regarded as sacred, and as inviolable as any other species of property.

Even Christians Recognised Slavery.

So deeply rooted and so universally received was this conviction that the Christian religion itself, though it recognised no distinction between Jew and Gentile, between slave or freeman, cautiously abstained from denouncing slavery itself as an injustice or a wrong. It prudently tolerated this crying evil, because in the state of public feeling then existing, and at the low standard of enlightenment and intelligence then prevailing, it was simply impossible to remedy it.

Thus then had slavery come down almost to our own time as an established social institution, carrying with it the practical sanction and approval of ages and nations, and surrounded with a prestige of standing and general acceptance well calculated to recommend it to men’s feelings and sympathies. And yet it was the embodiment of the most odious and cruel injustice that ever afflicted humanity. To claim a right of property in man was to lower a rational creature to the level of the beast of the field; it was a revolting and an unnatural degradation of the nobility of human nature itself. (etc, see link)

Back to the land

Nulty rose to become the Most Reverend Bishop of Meath and was known as a fierce defender of the tenant rights of Irish tenant farmers throughout the 34 years that he served in that office from 1864 to 1898.[5][6] Thomas Nulty is famed for his 1881 tract Back to the Land, wherein he makes the case for land reform of the Irish land tenure system.[7] Nulty was a friend and supporter of the Irish nationalist Charles Stewart Parnell until Parnell's divorce crisis in 1889.[8][9]

Dr. Thomas Nulty, who had attended the First Vatican Council in 1870, said his last mass on December 21, 1898.

To the Clergy and Laity of the Diocese of Meath:

Dearly Beloved Brethren,-

I venture to take the liberty of dedicating the following Essay to you, as a mark of my respect and affection. In this Essay I do not, of course, address myself to you as your Bishop, for I have no divine commission to enlighten you on your civil rights, or to instruct you in the principles of Land Tenure or Political Economy. I feel, however, a deep concern even in your temporal interests — deeper, indeed, than in my own; for what temporal interests can I have save those I must always feel in your welfare? It is, then, because the Land Question is one not merely of vital importance, but one of life and death to you, as well as to the majority of my countrymen, that I have ventured to write on it at all.

With a due sense of my responsibility, I have examined this great question with all the care and consideration I had time to bestow on it. A subject so abstruse and so difficult could not, by any possibility, be made attractive and interesting. My only great regret, then, is that my numerous duties in nearly every part of the Diocese for the last month have not left me sufficient time to put my views before you with the perspicuity, the order and the persuasiveness that I should desire. However, even in the crude, unfinished form in which this Essay is now submitted to you, I hope it will prove of some use in assisting you to form a correct estimate of the real value and merit of Mr. Gladstone’s coming Bill.

For my own part, I confess I am not very sanguine in my expectations of this Bill — at any rate, when it shall have passed the Lords. The hereditary legislators will, I fear, never surrender the monopoly in the land which they have usurped for centuries past; at least till it has become quite plain to them that they have lost the power of holding it any longer. It is, however, now quite manifest to all the world — except, perhaps, to themselves — that they hold that power no longer.

We, however, can afford calmly to wait. While we are, therefore, prepared to receive with gratitude any settlement of the question which will substantially secure to us our just rights, we will never be satisfied with less. Nothing short of a full and comprehensive measure of justice will ever satisfy the tenant farmers of Ireland, or put an end to the Land League agitation.

The people of Ireland are now keenly alive to the important fact that if they are loyal and true to themselves, and that they set their faces against every form of violence and crime, they have the power to compel the landlords to surrender all their just rights in their entirety.

If the tenant farmers refuse to pay more than a just rent for their farms, and no one takes a farm from which a tenant has been evicted for the non-payment of an unjust or exorbitant rent, then our cause is practically gained. The landlords may, no doubt, wreak their vengeance on a few, whom they may regard as the leaders of the movement; but the patriotism and generosity of their countrymen will compensate these abundantly for their losses, and superabundantly reward them for the essential and important services they have rendered to their country at the critical period of its history.

You know but too well, and perhaps to your cost, that there are bad landlords in Meath, and worse still in Westmeath, and perhaps also in the other Counties of this Diocese. We are, unfortunately, too familiar with all forms of extermination, from the eviction of a Parish Priest, who was willing to pay his rent, to the wholesale clearance of the honest, industrious people of an entire district. But we have, thank God, a few good landlords, too. Some of these, like the Earl of Fingal, belong to our own faith; some, like the late Lord Athlumny, are Protestants; and some among the very best are Tories of the highest type of conservatism.

You have always cherished feelings of the deepest gratitude and affection for every landlord, irrespective of his politics or his creed, who treated you with justice, consideration and kindness. I have always heartily commended you for these feelings.

For my own part, I can assure you, I entertain no unfriendly feelings for any landlord living, and in this Essay I write of them not as individuals, but as a class, and further, I freely admit that there are individual landlords who are highly honourable exceptions to the class to which they belong. But that I heartily dislike the existing system of Land Tenure, and the frightful extent to which it has been abused, by the vast majority of landlords, will be evident to anyone who reads this Essay through.

I remain, Dearly Beloved Brethren, respectfully yours,

+THOMAS NULTY.

BACK TO THE LAND

Our Land System Not justified by its General Acceptance.

Anyone who ventures to question the justice or the policy of maintaining the present system of Irish Land Tenure will be met at once by a pretty general feeling which will warn him emphatically that its venerable antiquity entitles it, if not to reverence and respect, at least to tenderness and forbearance.

I freely admit that feeling to be most natural and perhaps very general also; but I altogether deny its reasonableness. It proves too much. Any existing social institution is undoubtedly entitled to justice and fair play; but no institution, no matter what may have been its standing or its popularity, is entitled to exceptional tenderness and forbearance if it can be shown that it is intrinsically unjust and cruel. Worse institutions by far than any system of Land Tenure can and have had a long and prosperous career, till their true character became generally known and then they were suffered to exist no longer.

Human Slavery Once Generally Accepted.

Slavery is found to have existed, as a social institution, in almost all nations, civilised as well as barbarous, and in every age of the world, up almost to our own times. We hardly ever find it in the state of a merely passing phenomenon, or as a purely temporary result of conquest or of war, but always as a settled, established and recognised state of social existence, in which generation followed generation in unbroken succession, and in which thousands upon thousands of human beings lived and died. Hardly anyone had the public spirit to question its character or to denounce its excesses; it had no struggle to make for its existence, and the degradation in which it held its unhappy victims was universally regarded as nothing worse than a mere sentimental grievance.

On the other hand, the justice of the right of property which a master claimed in his slaves was universally accepted in the light of a first principle of morality. His slaves were either born on his estate, and he had to submit to the labour and the cost of rearing and maintaining them to manhood, or he acquired them by inheritance or by free gift, or, failing these, he acquired them by the right of purchase — having paid in exchange for them what, according to the usages of society and the common estimation of his countrymen, was regarded as their full pecuniary value. Property, therefore, in slaves was regarded as sacred, and as inviolable as any other species of property.

Even Christians Recognised Slavery.

So deeply rooted and so universally received was this conviction that the Christian religion itself, though it recognised no distinction between Jew and Gentile, between slave or freeman, cautiously abstained from denouncing slavery itself as an injustice or a wrong. It prudently tolerated this crying evil, because in the state of public feeling then existing, and at the low standard of enlightenment and intelligence then prevailing, it was simply impossible to remedy it.

Thus then had slavery come down almost to our own time as an established social institution, carrying with it the practical sanction and approval of ages and nations, and surrounded with a prestige of standing and general acceptance well calculated to recommend it to men’s feelings and sympathies. And yet it was the embodiment of the most odious and cruel injustice that ever afflicted humanity. To claim a right of property in man was to lower a rational creature to the level of the beast of the field; it was a revolting and an unnatural degradation of the nobility of human nature itself. (etc, see link)

Back to the land

Land: IRL

Stop Harassing Writer Akram Aylisli - Authorities Should Protect Author, Uphold Free Speech

ID: 201302121058

FEBRUARY 12, 2013

(Moscow) – The Azerbaijani government should immediately end a hostile campaign of intimidation against writer Akram Aylisli. Aylisli recently published a controversial novel depicting relationships between ethnic Azeris and Armenians in Azerbaijan.

Foreign governments and intergovernmental organizations of which Azerbaijan is a member should speak out against this intimidation campaign. They should urge the authorities to immediately investigate those responsible for threats against Aylisli, and to respect freedom of expression.

“The Azerbaijani authorities have an obligation to protect Akram Aylisli,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Instead, they have led the effort to intimidate him, putting him at risk with a campaign of vicious smears and hostile rhetoric.”

Aylisli, a member of the Union of Writers of Azerbaijan since the Soviet era, is the author of Stone Dreams. The novel includes a description of violence by ethnic Azeris against Armenians during the 1920s, and at the end of the Soviet era, when the two countries engaged in armed conflict. Aylisli told Human Rights Watch that he saw the novel as an appeal for friendship between the two nations. The novel was published in Friendship of Peoples, a Russian literary journal, in December 2012.

Azerbaijan and Armenia fought a seven-year war over Nagorno-Karabakh, a primarily ethnic Armenian-populated autonomous enclave in Azerbaijan. Despite a 1994 ceasefire, the conflict has not yet reached a political solution. Against the background of the unresolved nature of the conflict, Aylisli’s sympathetic portrayal of Armenians and condemnation of violence against them caused uproar in Azerbaijan. An escalating crescendo of hateful rhetoric and threats against Aylisli started at the end of January 2013, culminating in a February 11 public statement by Hafiz Hajiyev, head of Modern Musavat, a pro-government political party. Hajiyev publicly said that he would pay AZN10,000 [US$12,700] to anyone who would cut off Aylisli’s ear.

“Azerbaijan’s authorities should immediately investigate and hold accountable anyone responsible for making threats against Aylisli, and ensure his personal safety,” Williamson said.

On January 29, officials from the Yeni Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan’s ruling party, publicly called on Aylisli to withdraw the novel and ask for the nation’s forgiveness. Aylisli told Human Rights Watch that two days later, a crowd of about 70 people gathered in front of his home, shouting “Akram, leave the country now,” and “Shame on you”, and burned effigies of the author. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that police were present but made no effort to disperse the crowd. No damage was done to Aylisli’s home.

In a speech about Aylisli’s book, a high level official from Azerbaijan’s presidential administration said that, “We, as the Azerbaijani people, must express public hatred toward these people," a comment that appeared aimed at Aylisli.

During a February 1 session, some members of Azerbaijan’s parliament denounced Aylisli, called for him to be stripped of his honorary “People’s Writer” title and medals, and demanded that he take a DNA test to prove his ethnicity. On February 7, President Ilham Aliyev signed a decree stripping Aylisli of the title, which he had held since 1998, and cutting off his presidential monthly pension of AZN1000 [US$1,270], which he had drawn since 2002. Aylisli learned of the presidential decree from television news.

In the wake of the public vitriol, Aylisli’s wife and son were fired from their jobs. On February 4, a senior officer at Azerbaijan’s customs agency forced Najaf Naibov-Aylisli, Aylisli’s son, to sign a statement that he was “voluntarily” resigning from his job as department chief. Aylisli told Human Rights Watch his son had received no reprimands during his 12 years on job.

“My son had nothing to do with politics,” Aylisli said. “In fact he always advised me not to write about politics and never agreed with my political views.”

On February 5, Aylisli’s wife, Galina Alexandrovna, was forced to sign a “voluntary” statement resigning from her job at a public library, following an inspection announced several days before.

Public book burnings of Aylisli’s works, some organized by the ruling party, have taken place in several cities in Azerbaijan.

“The government of Azerbaijan is making a mockery of its international obligations on freedom of expression,” Williamson said. “This is shocking, particularly after Azerbaijani officials flocked to Strasbourg last month to tout the government’s human rights record at the Council of Europe.”

The European Court of Human Rights has issued numerous rulings upholding the principle that freedom of speech also protects ideas that might be shocking or disturbing to society. In a judgment handed down against Azerbaijan, in a case that dealt speech related to the Nagorno Karabakh conflict, the court said, “[F]reedom of information applie[s] not only to information or ideas that are favorably received, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb.”

(Moscow) – The Azerbaijani government should immediately end a hostile campaign of intimidation against writer Akram Aylisli. Aylisli recently published a controversial novel depicting relationships between ethnic Azeris and Armenians in Azerbaijan.